In June of 2016, Amber Traxler’s world cracked open in a way she never thought possible. Her ten–year–old son Jared, a boy she described as full of laughter and light, tried to take his own life. The details still live in her mind like a reel she cannot stop, the creak of a locked door, her mother’s scream, the sight of her son’s small body leaning forward, face purple, lips lined with blood. She was thirty weeks pregnant at the time, helpless to do much more than cry for help while her mother and sister cut him down. The sound of her own voice screaming in the street, “My baby boy is gone,” is something she says she will never forget.

By the time the paramedics arrived, Jared had no pulse. He was airlifted to the children’s hospital and placed on life support, machines breathing for him, monitors blinking out an answer to the question everyone in that waiting room was too afraid to ask. The doctors braced Amber for the worst, telling her his brain showed no activity, his body was failing, and his chances were slim to none. They induced a coma, patched a collapsed lung, and tried to control fevers and dangerous drops in temperature. For nearly a week, Amber lived in that hospital chair, barely moving except to shower or grab a bite to eat. She sat with her freckle–faced boy, stroking his hair, whispering promises that she would not leave him, begging him to stay.

She kept thinking, how could this be her son? Jared had always seemed like such a happy child, the type to run barefoot in the yard, to light up rooms with his grin. Yes, he had grown moody after his beloved Papaw passed away the year before, but she thought it was grief, maybe just the turbulence of preteen years. He told her he was fine, and she believed him. What mother imagines suicide on the mind of a ten–year–old? She blamed herself, sitting in that hospital, wondering how she missed the signs, how she failed to see the depth of his pain.

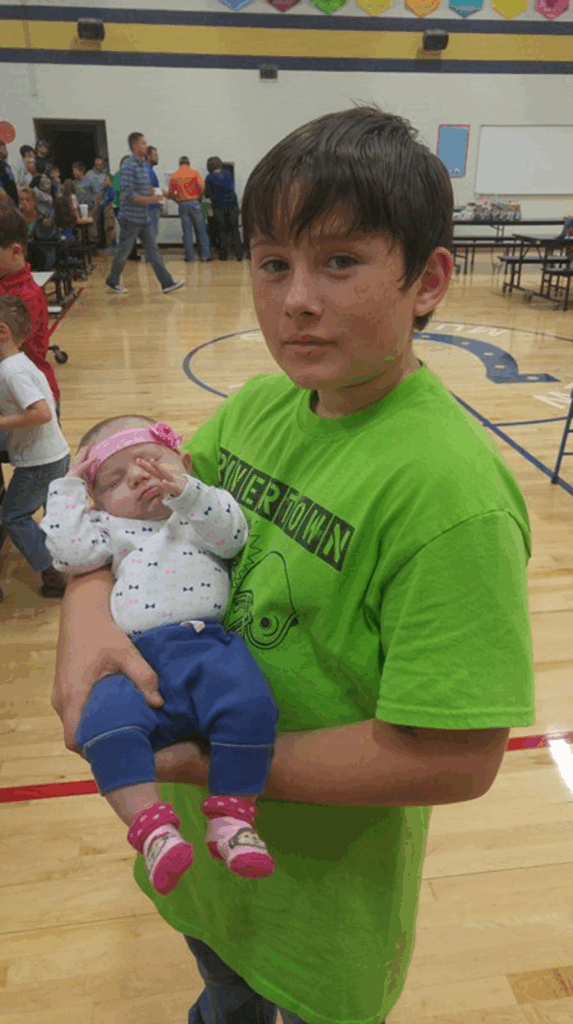

Then came the miracle she clings to even now. Against all medical odds, Jared opened his eyes. The doctors admitted they could not explain it. Children in his condition did not survive, yet here he was, slowly relearning to walk, to eat, to talk. Amber calls it nothing less than divine intervention, a gift she was given twice. “God not only blessed me with my son once, but twice,” she says. The gratitude is tangled with the memory of terror, but it is gratitude all the same.

Jared tells his part of the story now, in his own words, though with the blunt honesty only a child can manage. He remembers walking into his grandfather’s room at age nine, expecting to borrow a fishing pole, and finding his Papaw gone instead. That was the day, he says, depression began its quiet work. He never told anyone how heavy his heart felt, not really. He admitted missing his Papaw, but not the darkness that followed. One year later, he made “a permanent decision off a temporary emotion.” He tried to end his life.

He remembers waking up in the hospital, confused and surrounded by machines, his family told to prepare for the worst. But somehow he lived. The doctors said no one survives what he survived. Yet Jared did. Today he speaks openly about his second chance. He fishes when he feels low, leans into small joys, and tells anyone who will listen that no matter how crushing the weight feels, they are worthy of life.

Amber’s plea echoes his: suicide has no season, awareness cannot wait until tragedy strikes. She knows too well the sound of her mother’s scream, the sight of a locked door, the helplessness of begging in the street. She does not want another parent to learn that lesson like she did. And Jared, still young but wise in ways his years should not require, reminds others that there is still light to be found even in the thick of grief.

Because sometimes survival itself becomes the testimony, proof that darkness lies. Jared should not be here, yet he is. And both he and his mother say the same thing now, a line repeated with reverence and relief: he was found worthy enough to stay.