She didn’t give up on her daughter; she gave her more people to love her, and kept a place in that circle for herself. She didn’t plan on becoming a birth mom. In late 2013, a test turned pink, and she kept it to herself, pretending silence might make it untrue. When she finally told her boyfriend, they scheduled an abortion in D.C., only to learn she was too far along. The only option meant flying halfway across the country, which was impossible. Fear and a hard, clear truth rushed in: they weren’t ready to parent. Adoption became the path she hadn’t imagined, but would one day be grateful for.

She opened her laptop and was buried under agency websites and promises she didn’t know how to measure. Movies had taught her more about adoption than real life had, which is to say not much. At an OB/GYN visit, she mentioned adoption, got a pamphlet, and called the number. The agency listened. Papers were stacked up, including medical history, family details, and social background, and then came the profile books. She felt shallow sorting strangers into yes and no piles by photos, captions, and gut feeling. But one letter stopped her. Most began “Dear Expectant Parent” or “Dear Birth Mom,” formal and distant. This one began, “Dear Friend, we wonder if these letters are as hard to read as they are to write.” It felt like someone saw her as a person, not a gateway.

Not everyone did. When her dad learned she was pregnant and choosing adoption, he pulled away for years. Her mom relayed messages. “You made your bed,” someone said. She was told she couldn’t bring the baby home, as if love might make her change her mind. The judgment stung, but the plan held. She chose her top three families, then called her counselor to swap second and third, only to hear her first choice had already said yes. For the first time, things felt aligned: a respectful agency, the paperwork done, a family chosen. All that was left were birth and signatures.

Her due date slipped by. At 41 weeks, induction was scheduled, but the day before, labor started on its own. The birth dad came to the hospital. Contractions climbed until she folded into herself and cried; the epidural turned the room from storm to calm. She, her mom, and her birth dad watched the monitors like a TV show, guessing at other moms’ stories by the hills and valleys of their contractions. She pushed for about an hour and a half. At 6:30 p.m., a girl with wide, dark eyes arrived and made her mother. The baby was cleaned and measured. She didn’t feel worthy to hold her yet, so her mom looked first, only after asking permission.

The next evening, her counselor arrived. The baby slept on her chest while they talked, and she signed the termination of parental rights. It was the hardest right thing she had ever done. The day after, she went home with an empty belly and empty arms while her body still thought it needed to feed and hold a newborn. Eight days later, the revocation period ended. She could no longer change her mind and knew she wouldn’t. Love didn’t disappear; it just took a different shape. At placement, one moment etched itself into everyone’s memory: birth dad looked at their daughter, then at the adoptive father, and whispered, “It’s time to go to your dad now.” After that, the hours blur. She doesn’t remember where she slept or what she felt, only that life went on in small, stubborn steps.

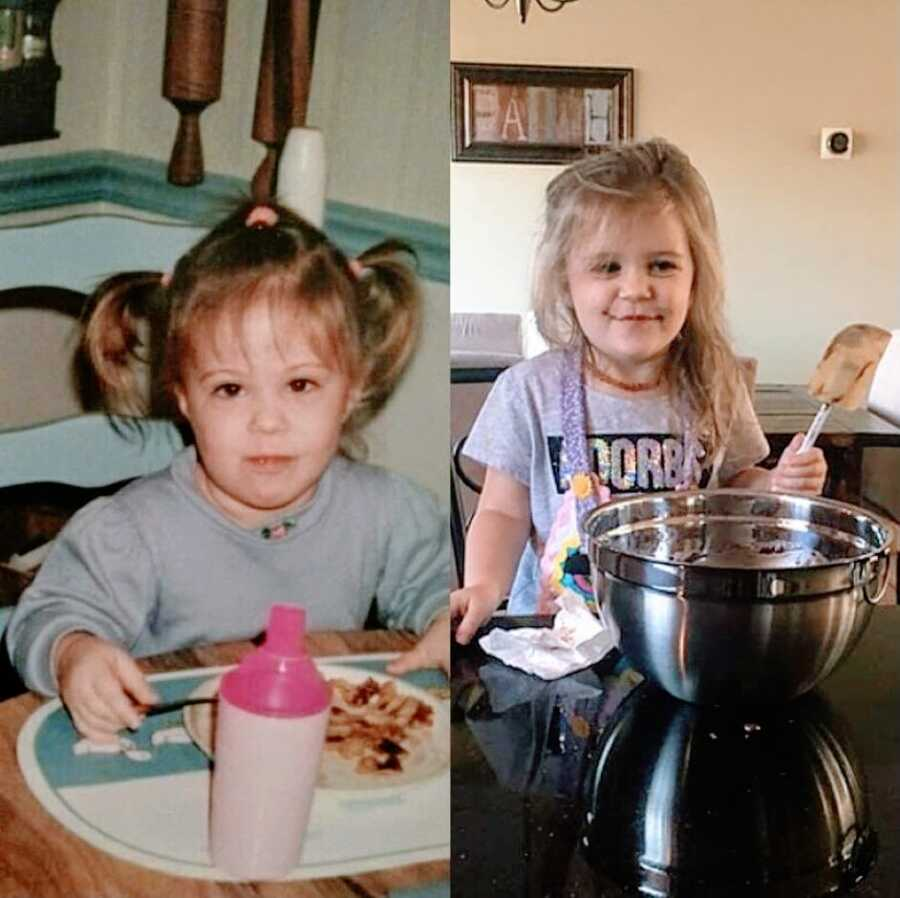

The years since have had rough patches, but they keep talking. They built an open adoption with a steady rhythm, photos every six months, visits every six months, alternating so something arrives every three. Their daughter knows who she is and where her names come from; at five, she could tell you her first name was a gift from her birth mom and her middle name from her parents. The resemblance shows up in side-by-side photos and a certain spark when she laughs.

When doubt creeps in, she repeats a few truths to herself: no two open adoptions look the same; being a birth mom isn’t a failing; relationships can grow after placement; and the adoption “constellation” is bigger than three people. Grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins can be woven in so that a child has more love and roots. Looking back, she still remembers the judgment, the late-night searches, the letter that called her “friend,” the baby’s warm weight while pens hovered over forms, and the quiet courage it took to leave the hospital without a car seat.

She also remembers the updates, the visits to parks and coffee shops, how her daughter runs in pink skates, and the relief of being seen, not as a mistake, but as a mother who chose a different kind of mothering.