She once ran from the part of her that felt different; now she wears it over her heart, art, memory, and a quiet vow to stand with her people, today and always. Slava Ukraini. She grew up in suburban New Jersey, calling herself American, trying hard to blend in at school. Her dad was American and her mom Ukrainian; the Ukrainian part felt big and strange when she was little. Family gatherings were full of a language she didn’t speak. Her Baba, grandmother, only spoke Ukrainian and did things in ways that felt “not normal” to a child. Wanting to fit in, she made one of her first life choices: she wouldn’t learn Ukrainian. It helped her feel less different at school and set her apart from her own family. She and her brother were the only ones who didn’t speak the language, and it quietly made her feel like an outsider.

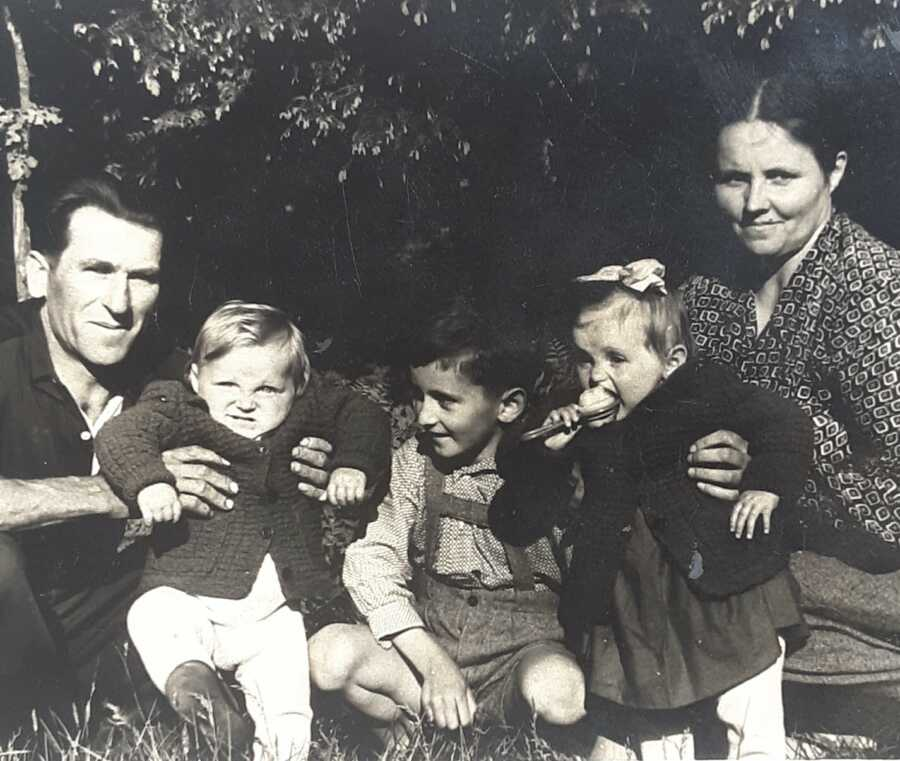

Time changed her view. The person who once scared her, Baba, was the one she resembled most. Baba had a kind of quiet “magic”: artistic hands, a deep intuition, a way of sensing things. As she grew older and understood her creative and sensitive nature, she realized she’d inherited Baba’s gifts. What had felt frightening when she was young was really her child-self picking up on something heavy: Baba’s pain. Baba had survived the unthinkable.

During World War II, her village was bombed and burned. She ran into the forest with her family; her mother froze to death there. As the eldest daughter, Baba kept four younger siblings alive, hiding food in the ground and enduring loss most people cannot imagine. Hearing this story as an adult, she finally understood the fear she’d felt as a child; it wasn’t Baba she feared. It was the weight of grief she could think without having words for it.

When Russia invaded Ukraine again, she couldn’t stop crying. It felt as if her ancestors were weeping through her. News clips looked like her grandmother’s memories happening in real time: people fleeing to Poland, families split, homes destroyed. The history she once thought of as far away stood suddenly in the present. And yet, the same traits she’d seen in her family- iron will, soft heart, fierce loyalty- seemed to shine in Ukrainians everywhere, with flowers in their hair, yes, but the spirit of warriors.

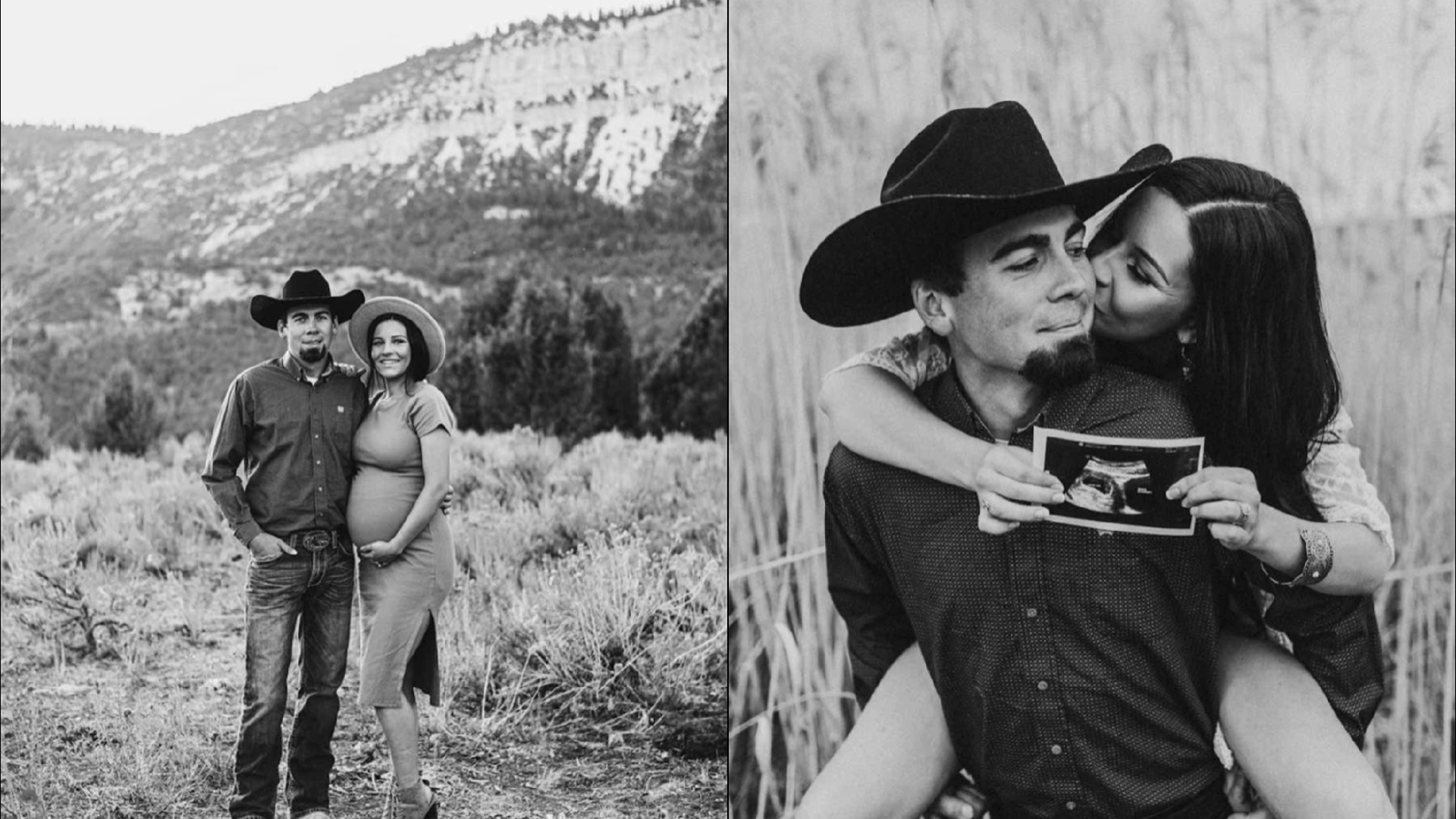

Craft runs deep in that culture. Baba was a gifted textile artist who stitched beauty into the world despite everything she had lived through. She made embroidered shirts and tapestries, and those pieces became heirlooms. From her, the granddaughter got art in her bones too, and she is now a metalsmith and jeweler by trade. In the first days of the new war, she went to her studio and let her hands lead. She designed a Tryzub pendant, the Ukrainian trident, the national coat of arms, as a small, intense prayer for peace. Jewelry, she believes, can connect people and amplify intention. The Tryzub, to her, is a sign of the inner warrior standing up to protect home, language, and love. As she worked, she could almost feel Baba beside her.

She decided each pendant would send $100 to humanitarian aid in Ukraine through the Ukrainian National Women’s League of America, an organization dear to her family. Her aunt Roksolana had been active with the UNWLA and had gone to Ukraine after a previous invasion to help wounded soldiers and families. Knowing the donations go directly where needed made the project feel right.

It became a way to honor her heritage and turn grief into relief. Looking back, she can see the arc clearly: the child who avoided a language to fit in, the young woman who slowly recognized the beauty and pain in her roots, the artist who now carries both with pride. She still doesn’t speak Ukrainian, but she understands what it means to belong to a people who keep creating, loving, and standing back up. She wears her Tryzub, thinks of Baba’s steady hands, and whispers a simple blessing that carries generations inside it.