After losing her baby, Meaganne found that the world kept moving, but her own had stopped somewhere between the hospital bed and the quiet drive home. The memory of that sterile room still lived behind her eyelids, the machines, the soft cries, the sterile air. She had walked in as a mother-to-be and walked out with empty arms.

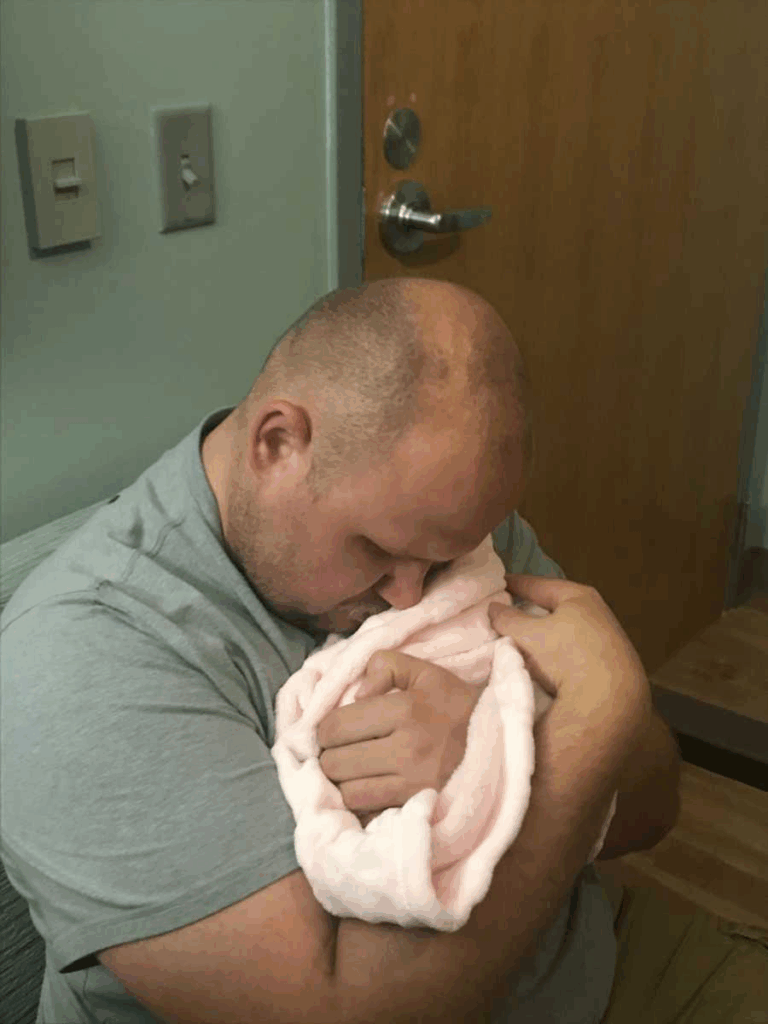

Her daughter, Charlotte, had come into the world far too early, a tiny miracle who weighed barely more than a pound. For a few fleeting days, she fought. Five days later, her heart gave out, leaving behind parents who had memorized every fragile detail, her fingers, her eyelashes, the faint rhythm of her chest. Child loss had entered their lives without warning, rewriting every plan they ever had. In the weeks after, grief wrapped around Meaganne like a heavy coat she couldn’t take off. She woke each morning forgetting for a second, then remembering, and feeling her chest sink. The house was quiet; her arms were empty. The baby clothes stayed folded in drawers, untouched.

And then came the anxiety. It started as small tremors, the kind she tried to brush off. But soon, it became a storm that moved in without permission. At first, she told herself it was normal, maybe she was tired. But one night, when her husband was away at work, her heart began to race for no reason. Her thoughts spiraled into fear, what if she lost him too? She couldn’t breathe, focus, or stop the trembling. It was her first anxiety attack, though she didn’t have a name for it then.

Child loss changes everything, even how a person walks through an ordinary day. At her postpartum checkup, a well-meaning receptionist smiled and asked about the baby. The question hit her like a wave. She shook her head. There was no baby. The air in that waiting room felt thick, and she could feel people’s eyes on her, even if they weren’t actually looking. Anxiety has a way of amplifying silence, turning it into noise. Later, when her doctor asked what made her anxious, she had to explain again. Saying it out loud felt like reopening a wound. Grief has layers, and so do anxiety, sadness, guilt, and fear, all folding in on themselves.

At home, surrounded by family, she still felt the ache. There were moments when she laughed at her parents’ lake house, tried to be present, even gave gifts in memory of her baby — tiny imprints of Charlotte’s feet pressed into a necklace and keychain. But joy and grief can live side by side, and sometimes they collide. She found herself crying in front of her family and immediately felt embarrassed. Later that night came another attack, more potent than the first. Her chest tightened, her muscles locked, her breath refused to come.

Anxiety after child loss is not just mental; it’s physical. Her body remembered what her heart couldn’t process. She clawed at her skin, pressed her fingers into her knees, trying to feel something she could control. Her husband held her hands, whispered for her to breathe. In those moments, she wasn’t just grieving her daughter; she was fighting her own body. The cycle repeated, some nights calm, others full of panic. Each attack made her weaker but more aware that she couldn’t do this alone. Anxiety after loss, she learned, doesn’t just disappear; it has to be managed, understood, and treated with care.

She began to speak openly about it, refusing to hide behind shame. She started medication, sought therapy, and learned that asking for help wasn’t a weakness, it was survival. Because living with grief is exhausting, smiling when her heart ached was exhausting. Pretending everything was okay was exhausting.

Some days, she woke up grateful; others, she walked through the hallways at work trying not to cry. But each day, she moved forward. Slowly, painfully, courageously. Child loss had taken her daughter, but it had also carved out a new version of her, one that knew grief and anxiety were not signs of failure but proof of love that refused to fade. She was learning to live again, one heartbeat, one breath, one day at a time.