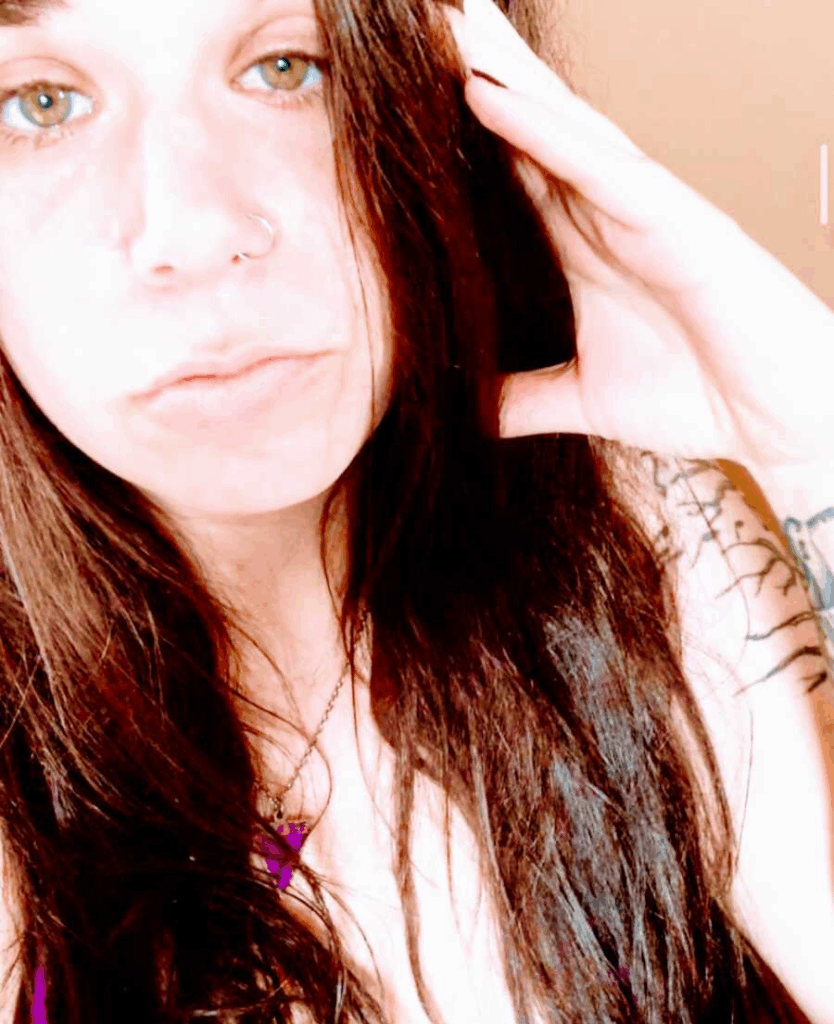

Epilepsy changed her life, but it did not end it. With the right team, better tools, and people to lean on, she chose to live forward and to help the next person do the same. She was an ordinary teenager on the verge of college life when everything shifted. At eighteen, she drove siblings to school, worked, and planned her future. Then one morning, she crumpled to the floor and woke up in bed hours later with no memory. More spells followed. Friends noticed strange moments, mostly at night. She had always thought seizures meant flashing lights and dramatic convulsions, so she brushed off the idea. She learned the hard truth later: there are many kinds of seizures, most without strobe lights, and some are almost invisible unless you know what to look for.

No one in her family had epilepsy. She had no head injury, no tumor, no lesions. The tests initially showed nothing, and relatives argued over what they had seen. She was frightened and confused. Doctors eventually named it idiopathic epilepsy, which means there is no apparent cause. On top of that, her seizures did not respond to medicine alone. Each time she stayed seizure-free long enough to reclaim a little freedom, like driving or working, a split second would take it away again. The losses weighed on her mental health, and a few medications made her darker and more hopeless than she had ever been. Hope took shape when she was referred to a specialized seizure center at UCLA. Experts listened, tracked patterns, adjusted medicine, and gave her language for what was happening inside her brain. They also raised a new option she had never considered: brain surgery. The idea was terrifying and relieving at the same time. After years of trial and error, she finally had a plan.

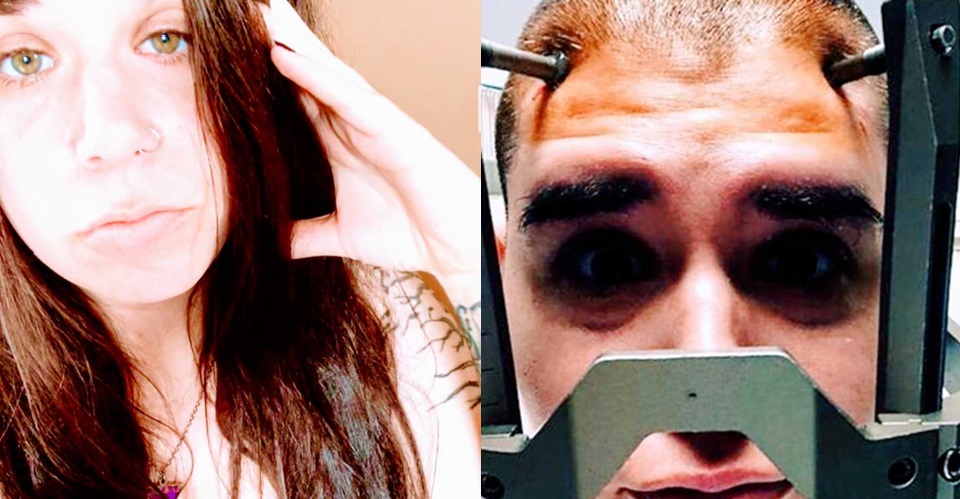

The road to surgery was long. She spent days in a monitoring unit trying to capture seizures on video and an EEG. She completed strict neuropsych testing to protect her thinking and memory. She traveled to San Francisco for a MEG scan, a magnet-based map that could show where seizures might begin. She cleared a functional MRI and CT. The hardest step was a stereo EEG, where surgeons placed thin electrodes deep in her brain and watched for over two weeks. She was shaved, exhausted, nauseated, and vulnerable. But the data told the story her team needed. She qualified for an implanted responsive neurostimulator, or RNS.

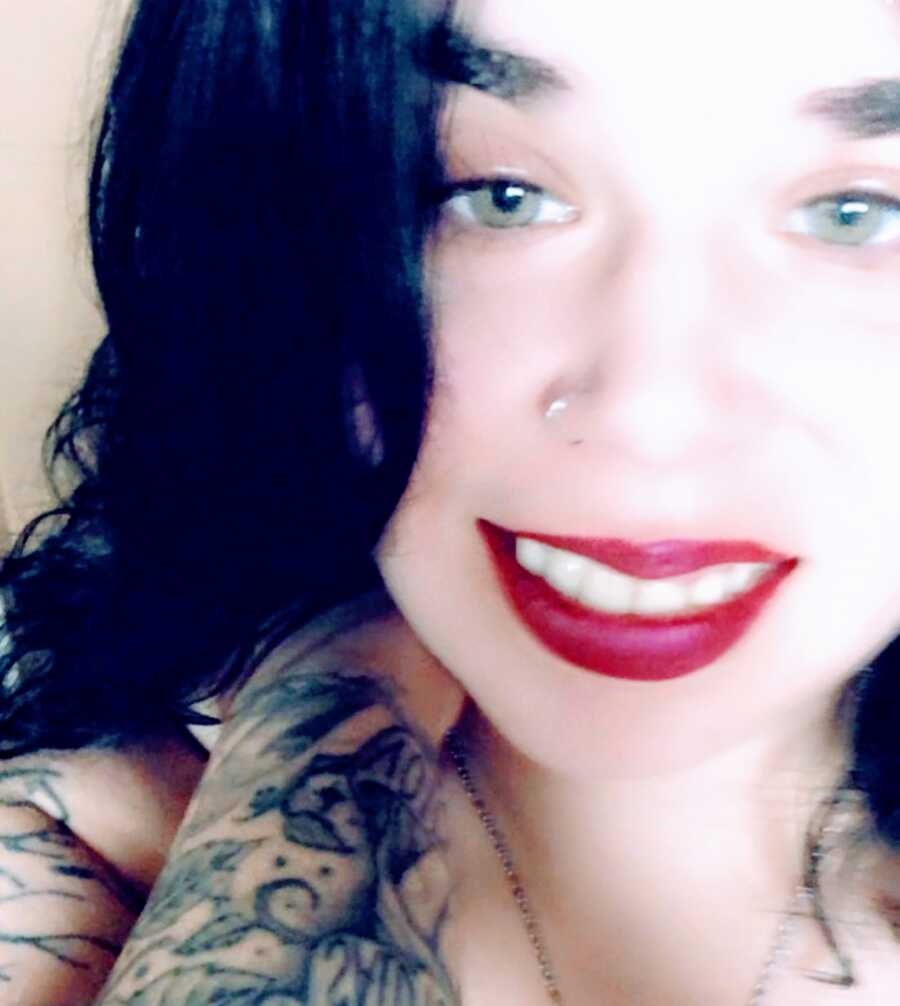

The RNS is like a pacemaker for her brain. Surgeons created a small shelf in her skull for the device and threaded electrodes to the seizure hot spots in her temporal lobe and hippocampus. The device records brain waves and delivers a tiny pulse when it senses a seizure pattern, interrupting the event before it blooms. She cannot feel it. She can feel the shift from constant fear to a steady sense of control. There is no cure yet, but for the first time, she has something that fights back.

Surgery also changed how she sees herself. Epilepsy is part of her life, not her fault. She did not cause it and cannot will it away, but she can choose how much room it gets. The diagnosis has made her more patient, more empathetic, and more open to others who live with hidden battles. She discovered that most people with epilepsy are not photosensitive and that many seizures are quiet to the eye. She learned there are millions of people in the United States alone who understand the strange mix of fear, hope, and grit that comes with this condition.

For twelve years she tried to carry it alone. Now she reaches out on purpose. She builds spaces where someone newly diagnosed can find a friend who speaks the same language. She wants people to hear the word epilepsy and think human, not danger. She wants the next eighteen-year-old who wakes up after a fall to know that help exists, options exist, and community exists.