When the world shut down during COVID, Garon Wade finally found the space to look back on his life. With long, lonely months stretching ahead, he began writing a memoir one that few others could tell. His story began in 1985, in Sri Lanka, during the height of a bloody civil war. As a baby, he was left on the steps of a hospital in the town of Kegalle. Whether it was his mother who placed him there, or whether he was taken from her, is something he still wonders about. For years, he imagined her walking quietly through the dawn, setting him down gently before vanishing into the morning shadows.

By the following year, fate had carried him into the arms of two Americans. Steve and Niki Wade, an adventurous couple who had already adopted a little girl while living in the Philippines, walked into the Jayamani Center in Colombo looking for a son. Niki was small, with a bright smile and an anthropologist’s hunger to understand people.

Steve was tall, athletic, and warm. They had started as a homecoming queen and football player in Louisiana, but their time in the Peace Corps in Botswana had changed them forever. They never stopped moving. In October 1986, after months of waiting and paperwork, they carried ten-month-old Garon out of the orphanage and into a life that would cross continents.

His childhood was as colorful as it was complicated. The Wades raised their family in South Africa, Hawaii, The Gambia, Jordan, and Louisiana. Their homes were surrounded by diplomats, aid workers, teachers, and kids from every corner of the globe. Each new country brought beauty cultures to learn, friendships to form but also heartbreak, because every few years they had to pack up and leave it all behind. For Garon, boarding another plane always came with the bittersweet pull of adventure on one side and loss on the other.

But not all of it was romantic. Life abroad meant facing dangers many children never imagine. In The Gambia, Garon once found himself staring at the barrel of a soldier’s gun, powerless and afraid. Years later, in the aftermath of September 11th, he lived with the shadow of Al-Qaeda’s terror. As a teenager, he mourned a friend killed by extremists. As an adult, he witnessed violence again when people were murdered at his workplace. Each time, he was pulled back to that sandy road in Africa, the memory of a weapon pointed at him never far away.

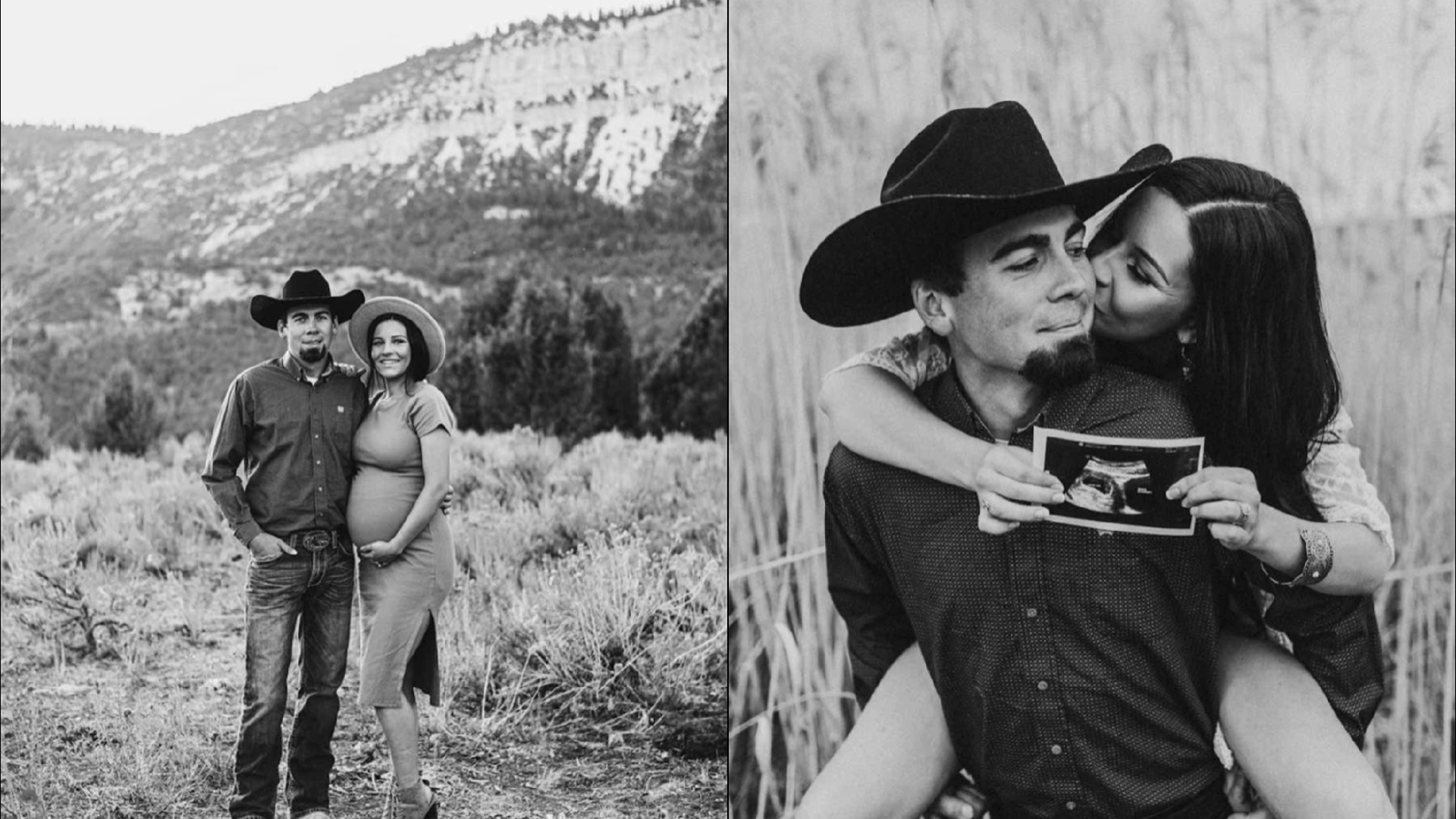

Still, Garon’s upbringing also shaped him in ways that brought strength and clarity. His mother, who worked as a sex-education teacher, spoke openly about topics many parents avoided. That openness gave him freedom from shame and encouraged him to live authentically. Now, as a father himself, he talks to his own sons about consent, relationships, and identity with the same honesty. In his house, love is not limited to one model, and he wants his children to grow up knowing they have the right to choose what happiness looks like for them.

Of course, his story is not only about survival and trauma. It is also about belonging, resilience, and hope. He writes about the thrill of international schools, the friendships that transcended borders, and the small details that made each place feel like home for a while. Yet he also admits the cost: the sadness of constant goodbyes, the weight of questions about his origins, and the grief of losses that never fully fade.

Today, Garon lives in the United States with his husband and their two sons. He works as an air traffic controller, guiding planes safely through the skies, even as his own life has been marked by turbulence. Friends sometimes tell him everything always seems to work out for him. He doesn’t agree it’s not luck, but rather the decision to keep choosing possibility despite pain.

As he puts it, sadness runs deep, but it also allows joy to shine brighter when it comes. In his memoir, You’ll Always Be White to Me, Garon captures this paradox: the delight and devastation of a life you can never fully predict. His journey from an abandoned infant in Sri Lanka to a father, husband, and storyteller reminds us that identity is not about where you start, but how you carry each piece of your story with you.