My name is Colleen, and I am an alcoholic’s daughter.

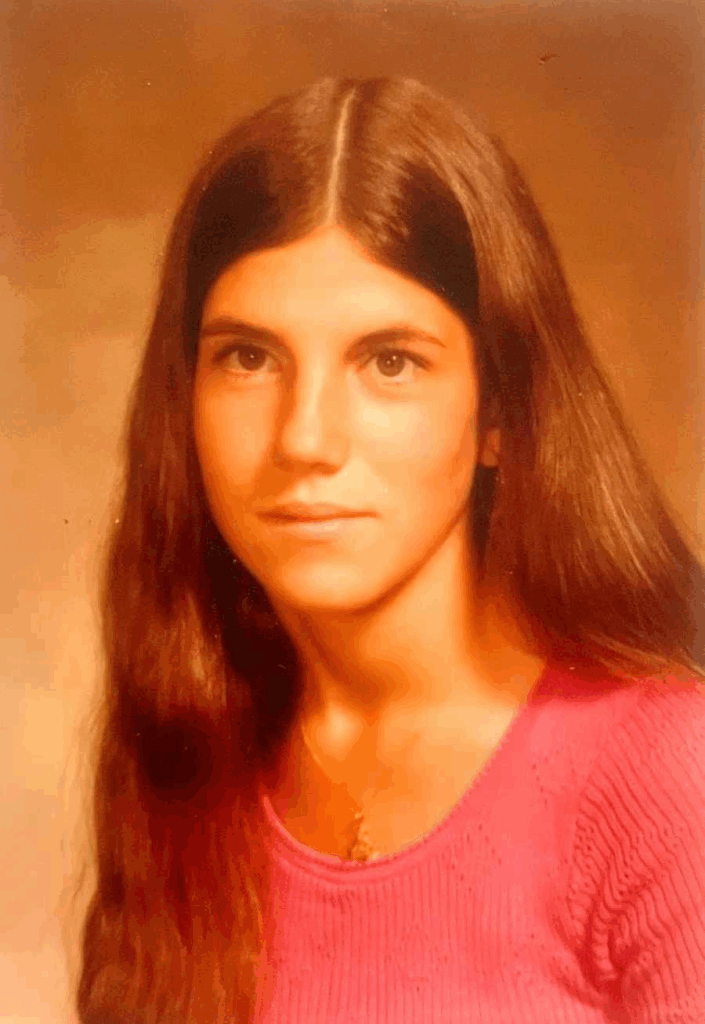

My mother was raised just beyond the suburbs of Boston, wrapped in warmth and love. In pictures I have seen, she appeared to be the sort of child everyone loved, bright eyes, lovely dresses, a smile. Her life on the surface appeared idyllic. But along the line, something cracked. In spite of the luxury of her upbringing, she fell into alcoholism, and that would dictate our lives in ways that I would never be able to escape.

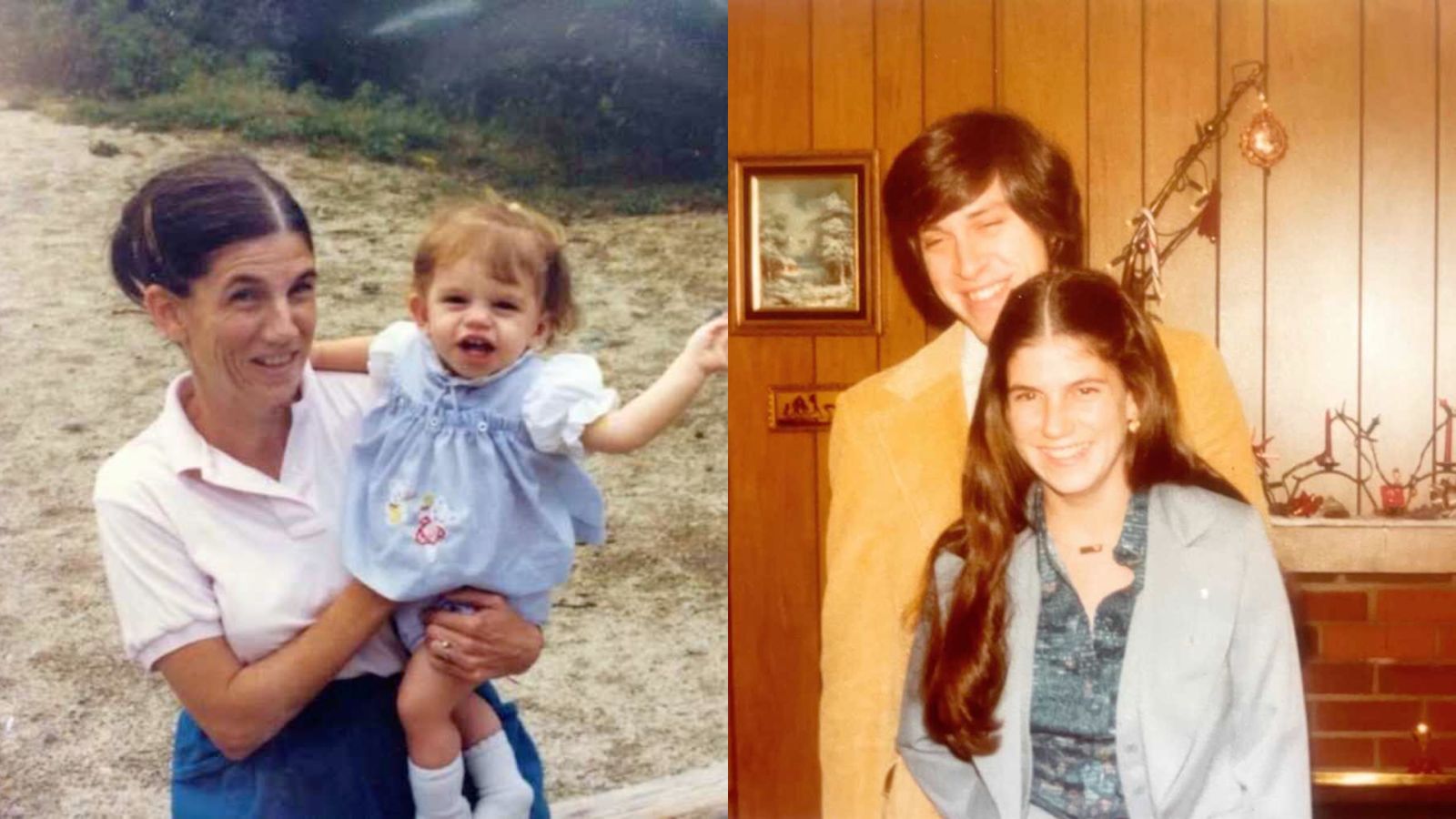

I don’t recall when the drinking started. From what they told me, she was already drinking before she married my dad. He was so in love with her, so much so that he ignored the warnings and married her anyway. They constructed a house together in a small town in New Hampshire, and after a while, I arrived.

Already as a little girl, I could feel that something was off. We would go to the supermarket every morning. She always had a purpose, milk, rice, something for supper, but it always ended up in the beer section with us. She’d grab a 12-pack, pass me a candy bar, and say, “Don’t tell Dad.” At home, her entire demeanor shifted. The glint in her eyes disappeared. Her tone became sharper. She’d flip between kisses and cruel words, giving me hugs telling me how much she loved me and accusing me of not loving her enough the next.

Evenings were the worst. I’d see her slumped over the couch, cigarette in her hand, the house smoky and yelled through. When Dad arrived home, I clung to him, he was safe. That made her madder, though. Their arguments would resound within the house for hours after I went to bed. Some nights, I’d put my head under the pillow, hoping to keep it quiet.

Mornings were confusing. Some mornings she still had a hangover, other mornings she was okay, drinking coffee with Dad like everything was normal. We never discussed it. No one ever used the word alcoholic. I learned about it on my own.

As I aged, my fear became anger. I dreaded those grocery store runs. One day, she drove us into a ditch. A stranger called the police, and I saw them take her away for driving under the influence. I was seven. I remember the flashing red lights, and her being taken away in handcuffs. This is the moment that I lost my trust in her. I pleaded with her to get help, but she would not even acknowledge that she had a problem.

School taught me that addiction was shameful, something only bad people did. No one spoke about trauma, about compassion, in the 90s. I began to think, because my mom was bad, maybe I was bad too. So, I remained silent.

There were bad times, though. She’d yell at me to do my homework, serve me stone-cold pizza on my birthday, or force me to go camping with her in the White Mountains. Those memories hurt all the worse because they reminded me of what she could have been. To love someone who is addicted is to live two worlds: one that is full of love, and the other of heartache.

Years went by, and her body started to deteriorate. She was coughing all the time, her memory slipping. We insisted that she go see a doctor, but she would not. When she did get sober, we began to mend. One day, she turned to me and said in a soft voice, “Colleen, I’m sorry for everything.” I did not know what to say. I just said it was alright. A few months later, she was dead.

It was destroying me, but it also liberated me. At her funeral, I was honest, I talked frankly about her addiction to alcohol. For the first time, I experienced a burden being lifted from my shoulders. I began sharing my story on the internet and connected with so many others who bore the same silence.

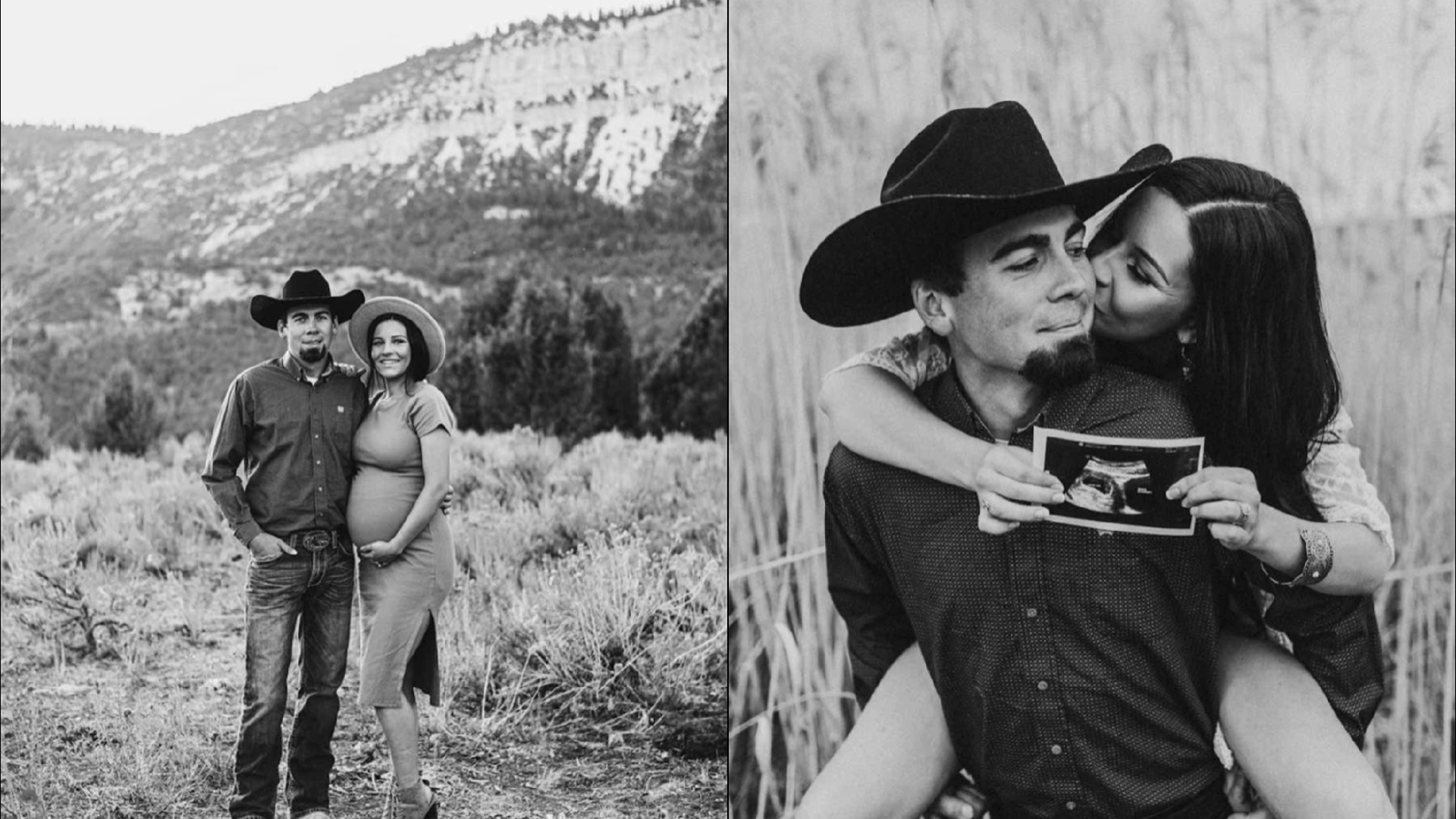

Sharing my truth did not take the pain away, but it set me free. I’ve realized that I can hold my mom accountable and still love her. She wasn’t always her addiction she was human, just like me. And in that knowledge, I finally healed.