I was born in 1967, and my mother had wanted me to be Anthony Ray. But things weren’t simple. I was born with both male and female traits, what we now call intersex. Doctors diagnosed me as a “pseudo-hermaphrodite,” meaning I had eggs but no sperm. Instead of being told I was simply a natural variation of humanity, they labeled me with a “disorder of sex development.”

My chromosomes are 46XX, which most people assume makes someone female. But I never felt like a woman, even though I was raised as one. They named me Antoinette. I was fortunate in one way, unlike many intersex children, I was not forced into cosmetic, non-consenting surgeries to “fix” my body. Still, I grew up in a world that erased who I really was.

From the time I was three, I was sent to therapy to “teach” me how to be a girl. Back then, doctors believed gender could be trained. If I acted like a “good girl,” I got stickers and candy bars. But by age four, something inside me broke. I became mute. They called it “selective mutism,” but to me it wasn’t a choice, I just felt erased, invisible, and alien.

By kindergarten, I begged my mom for a boy’s haircut, but I still lived in between. Girls didn’t accept me, boys didn’t either. I was a lonely child. My sister called me “Toni,” but even that name felt wrong. I wasn’t a girl, but I didn’t have the body of a boy either. I learned to “perform” being female, but deep down I knew I was different.

Medically, my body developed with a mix of male and female traits, small phallus, vulva, uterus, ovaries, even a partial prostate. By my teenage years, I carried a lot of shame and secrecy. People assumed I was just a tomboy or a butch lesbian. But the truth was simple: I liked boys. I would eventually marry a man named James, who loved me exactly as I was.

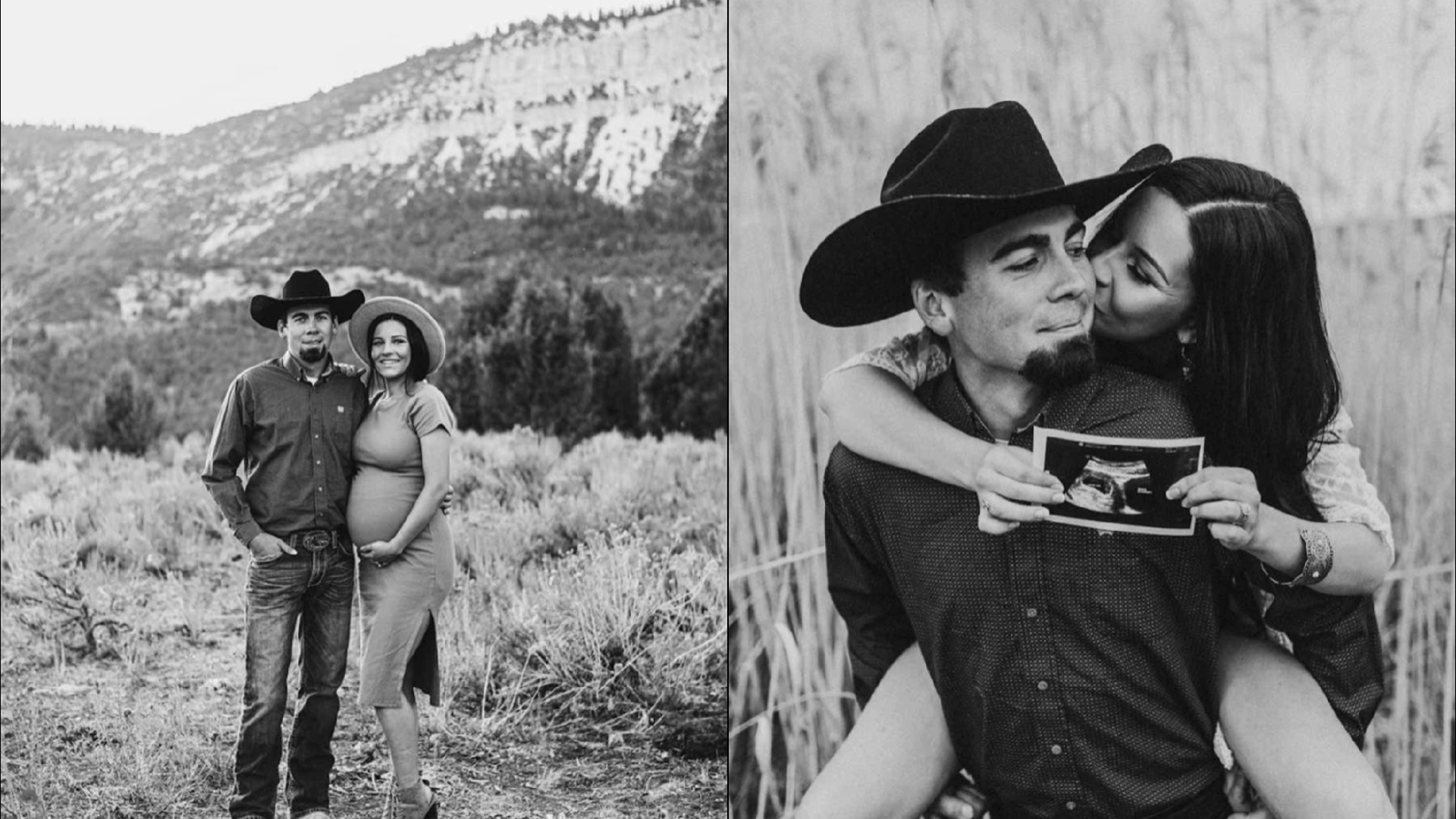

Life was not easy. I endured six pregnancies and four miscarriages, but with medical help I gave birth to two healthy babies a son and a daughter. Later, we adopted another daughter, and thanks to hormones and lactation support, I was able to breastfeed all three of my children. For me, this was an incredible joy. People might assume that makes me a woman, but no I was always intersex, and in my heart, I had always been a boy.

In 2014, everything shifted. Through the internet, I discovered the word “intersex” and began to connect the dots. I also learned about transgender men for the first time. Seeing them was life-changing. I realized I had been lied to: I could live as my true self, not as the girl I was forced to be. I wrote a letter to my husband telling him I would never live as a woman again.

At first, some support groups rejected me, intersex women didn’t like that I rejected my female assignment, and trans men didn’t always know what to do with an intersex man. I felt like an outsider, but I refused to hide. To me, “intersex” described my body, but my identity was simply male. Eventually, I found my voice, started my own group, and proudly called myself an intersex man.

My children began calling me “Vader” instead of mom, and for Mother’s Day we invented “Seahorse Day,” since male seahorses are the ones who give birth. I call myself a gestational father. My husband and I have been together for more than three decades. He says he’s “Anunnaki-sexual” because he loves me for exactly who I am.

In time, I embraced the name Anunnaki, inspired by mythological beings and also because “Anu” means ant and “Nnaki” means friend. It fit perfectly. I also stepped into activism. In 2018, I received the first intersex birth certificate in Colorado and later gave a TEDx talk, “Born Intersex: We Are Human.” My goal is to protect intersex children from unnecessary surgeries and to teach the world that we are a natural part of humanity.

Today, I’m proud of my body and my identity. I don’t feel trapped in the wrong body, I feel like I was always meant to be me. My vagina is part of me as a man. My chest that fed my babies belongs to me as a man. I am not broken. I am whole, and I am living proof that intersex is beautiful.