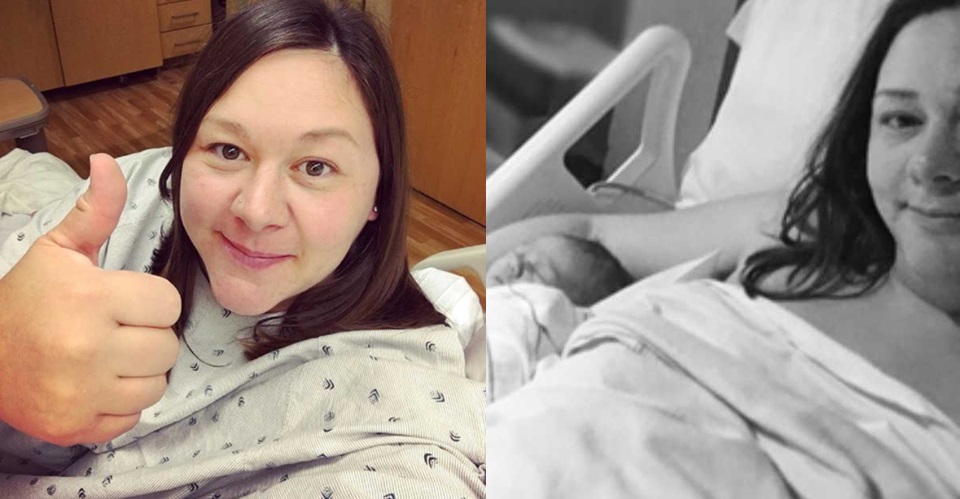

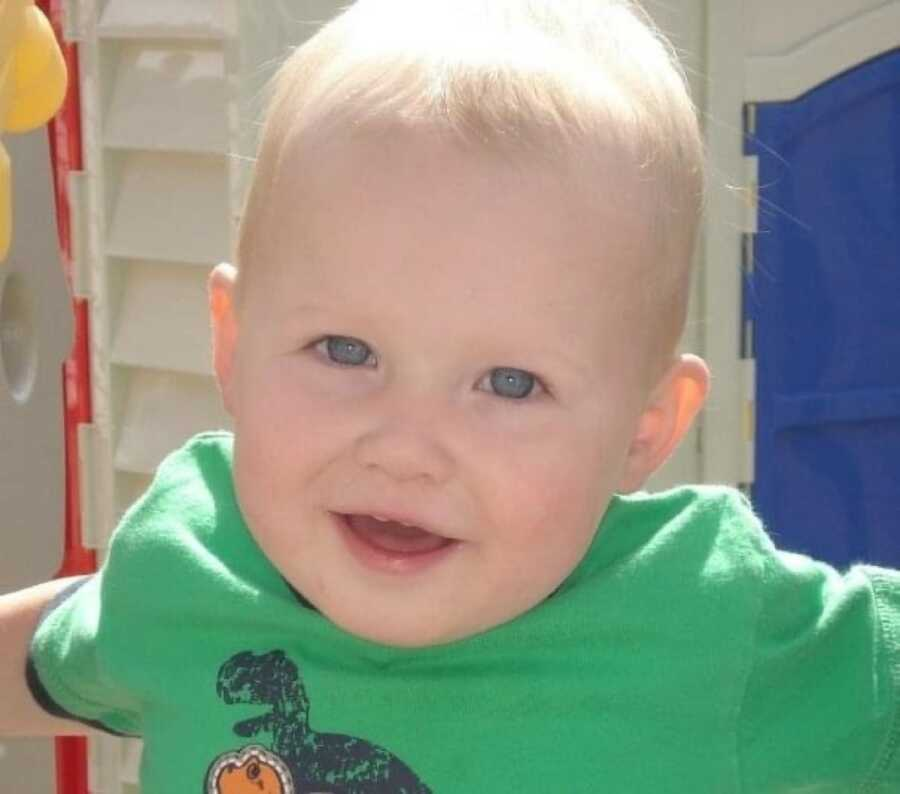

She once prayed for “normal.” Now she knows their miracle is Drew exactly as he is: kind, brave, and perfectly himself, lighting the way one honest, hopeful day at a time. They brought home a blue-eyed December baby and felt complete. Drew was easy to love, 8 pounds, 7 ounces of calm, sweet wonder, and life with two little ones began. It was messy and tiring, with diapers everywhere and a husband back at work too soon, but they found a rhythm. Around ten months, small worries crept in. Drew wasn’t cooing much or crawling, and tests showed sound wasn’t passing through his ears. At fourteen months, he got ear tubes. For a while, nothing seemed different. Then came strange shudders, like sudden chills, and the house grew quiet as everyone tried to understand what was happening.

Therapists came weekly. Drew learned some sign language and used picture charts to help with routines. By preschool, the shudders were happening many times daily, and balance was off. A sharp-eyed teacher noticed long, fixed stares and accidents. Her husband, a doctor, observed and suspected seizures. The first hospital EEG, short, noisy, not ideal, came back clear. But the signs didn’t stop, and a second, longer, sleep-deprived EEG with a pediatric neurologist finally named it: epilepsy.

They left the office in shock, holding hands and with questions. In the car, their little boy looked up and said, “Momma, I will be alright.” She cried then. The tests continued: a sedated MRI (she’d watched patients fall asleep a hundred times at work, but watching your own child is different), then a 24-hour video EEG. The diagnosis settled: absence seizures (the staring spells) and myoclonic seizures (the “chill” shudders). Medication started. So did years of labs, EEGs, home studies, and therapy. School was hard. Lessons had to be modified. Summer brought tutors and extra practice taped around the kitchen island. He learned, just not on the calendar anyone else used.

Still, life kept opening. Drew learned to ride a bike and zoom a scooter. He loved water with wild, fearless joy. Camping made him smile because there were always kids around. Classmates were kind, but invitations didn’t come. It hurts to answer, “Why won’t anyone play with me?” Older brother and his friends became his safe circle, and those moments felt like sunlight.

Fourth grade brought an evaluation that went badly and ended early, with a young school psychologist using labels that felt cold and wrong. She cried in that meeting, and so did the teacher. They sought a neuropsychologist instead. After long testing days, a thick report spelled out low IQ and limits, no four-year degree likely, maybe marriage, and probably a job with support. She felt anger rise. A number is not a child. He is sensitive and funny and deeply tuned to other people’s feelings. Many adults live good lives without college. Their measure would be joy, not letters after a name.

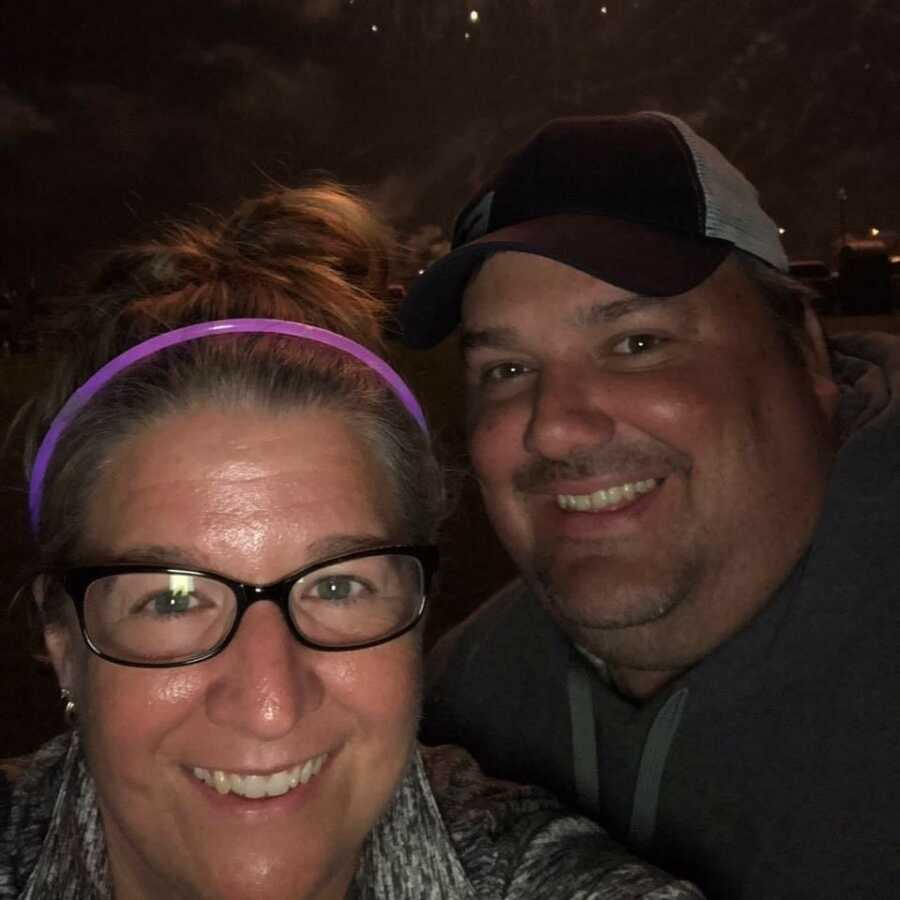

And there was good news too: a full year of normal EEGs. In 2018, the neurologist smiled and said, “Go have fun, Drew.” They celebrated with pizza and arcade noise and the rare quiet inside a parent’s chest when a weight lifts. For almost five years, he lived medication-free, everyone stretching into something like normal. Then, on January 27, 2022, it all crashed back. In the hallway at home, Drew had a grand mal seizure, his first. She cannot forget the sound of his breath or the way time slowed. Another seizure hit in the ER, dislocating his shoulder. Appointments: pediatrician, physical therapy, and another sleep-deprived EEG returned like a tide. They tried to live forward while their hearts kept glancing back, asking, “Are you okay?” too often because it felt like the only way to keep him safe.

Drew, as always, met it with grace. He didn’t ask “Why me?” He followed directions, cracked smiles, charmed nurses. He’s an old soul in a teenage body, teaching acceptance without speeches. He wants to give more than he takes. He loves fully. He is good to people because that’s who he is. They went over results, planned next steps, and kept life moving. He was confirmed at church. He danced twice, with a special friend. He finished the basketball season as the team manager, a job he owned with pride. Learning to drive was on the horizon; maybe it still is, perhaps it isn’t, but hope is a muscle they know well.

She still has moments where guilt whispers about pregnancy and missed signs. But she can see, more clearly now, everything they have done right: the advocacy, the patience, the laughter stitched into hard days. Drew will earn a certificate instead of a diploma, and that’s okay. He will work somewhere that feels like purpose. He may marry. He will love and be loved. The goal isn’t to fit a chart; it’s to build a life that fits him. If this journey has taught her anything, it is to slow down and borrow his eyes. Different isn’t less; sometimes it’s a better way to see the world. He is not about epilepsy or a score; he’s a boy with a heart that changes rooms, who keeps teaching his parents the courage of ordinary days.