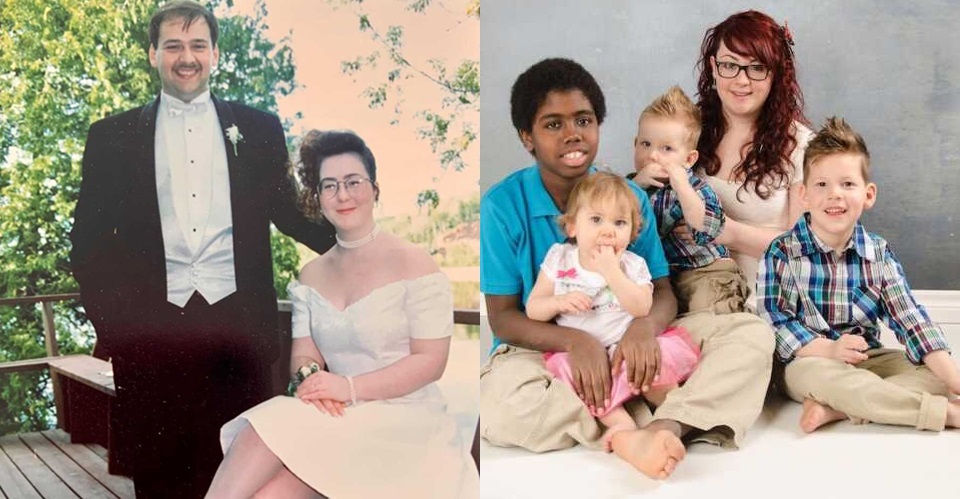

Tara and Paul married young with a simple plan: fill a big country house with children by the time she turned thirty. Life had other ideas; infertility crept in and stayed. They even sat through a foster-care info session, only to be handed stacks of forms that felt like strangers peering into their hearts.

Paul slid the papers into a cupboard with a “not now,” they turned back to doctors, schedules, and pills. Every pregnancy announcement from friends stung. Baby showers were impossible. She hated that jealousy lived beside her love for the people in her life, and she judged herself for feeling it.

Then one month, a nurse phoned with the words they had prayed for: she was pregnant. The joy was absolute, but so was the nausea that never left. Late in the pregnancy, her body threw up a red flag: preeclampsia, a swollen liver, and low platelets. And plans vanished.

There was a rush to induce, a room full of fear, and then a tiny cry. Their daughter, Parker Danielle, arrived at 4 pounds 10 ounces, with jaundice that made her look a little like a yellow frog and not a single fat roll to pinch. She was perfect. They took her home, held her close, and exhaled.

As Parker grew, they talked about more children. But the risks were no longer abstract. They had seen hospital monitors and heard words you can’t unhear. They tried the exact fertility needs that helped the first time. Instead of falling apart, they listened to her body and kept their hearts open to other paths.

They pulled those old papers from the cupboard and asked themselves hard questions. There were no private agencies in their small Canadian province, and they couldn’t advertise. Public adoption often meant sibling groups, and the wait for an infant was ten years, so they looked abroad.

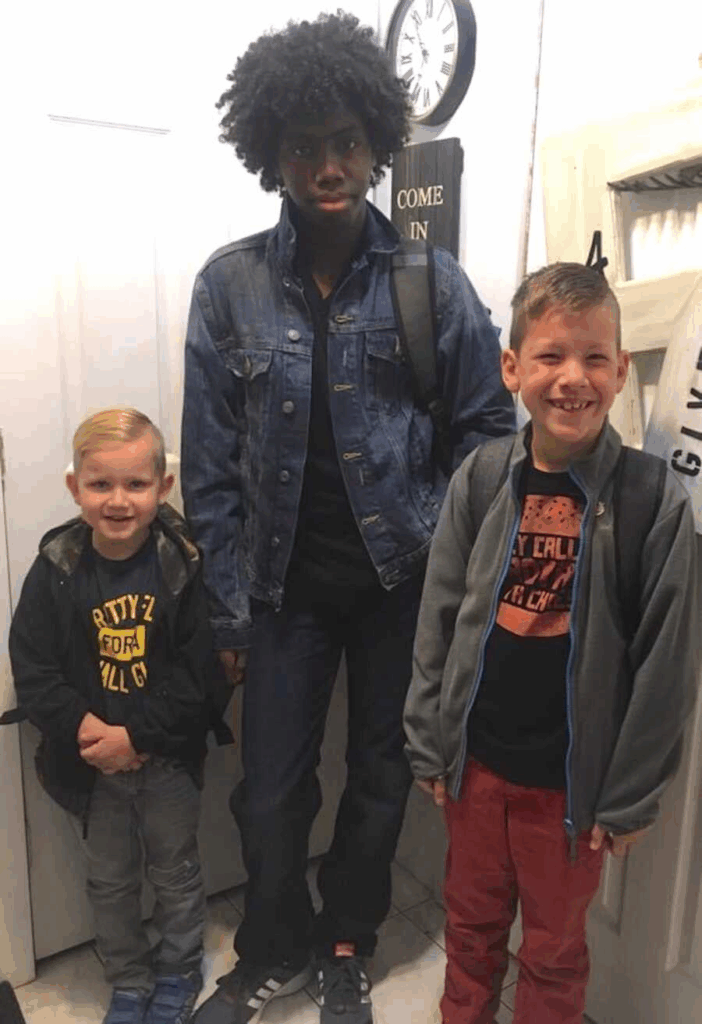

The United States was close, and a Georgia agency had a need. Soon, birth parents chose them; a son, Xavier, was waiting. Getting him home was its own adventure; flights fell through. An airline ambassador finally escorted the baby to Maine and drove across the border together. Xavier became theirs in every way, holding both Canadian and American citizenship. Paul took parental leave. She worked from home, and Parker wasn’t in school yet. That first year as four felt like a gift they’d never stop unwrapping.

A year later, she had a hysterectomy, which was right for her health; she had no regrets. They tried to adopt within Canada next, sending their profiles everywhere, but the doors stayed closed. So they opened their home as foster parents. Over five years, they cared for nine children, from babies to teens, singletons and siblings, arriving at all hours with little more than a name. The goal was always reunification. The small victories became a soft landing: doctor visits, school meetings, birthdays, holidays, long car rides to family visits, and lots of firsts. The small victories were everything: the first steady eye contact, the first hug, the trust that food would be there, and someone would show up.

Saying goodbye never got easier. If it didn’t hurt, they believed, they hadn’t done it right. But those years taught them to see past labels and paperwork and meet the child in front of them. Then came a call about a child “younger than expected.” A roundtable of workers and the foster family sat with them.

They agreed to keep the bond with their foster “nanny and papa.” Their boy came home just before his second birthday, not yet walking or talking but perfectly himself. Therapies began with speech, occupational, and physical therapy. An early Autism diagnosis brought clarity, not fear. They learned basic sign language, counted words, and watched him sprint from his first steps to school sports.

He was bright and easygoing and soon earned the nickname “Mr. Sunshine.” ADHD was part of his story, too, and they adjusted with love and structure. Another call, a baby brother needed a home, done. The little guy arrived at 16 months, a fearless spark who seemed powered by curiosity alone.

Over time, he received a diagnosis of Autism, ADHD, and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. School was bumpy, safety plans were constant, and their advocacy muscles grew stronger than they ever thought necessary. He kept them laughing and on their toes.

One year later, the phone rang again: a baby sister was available. At 14 months, she came home and stitched the final seam in their family fabric. The brothers adored her; she ran the house with a grin and a hand on everyone’s heart. Parker and Xavier, “the bigs” and the three “titles” turned the house into a happy kind of loud.

Neurodiversity made life busy and sometimes exhausting, but they wouldn’t trade it. They had become exactly what they dreamed of at the start, just by a different road, two by birth and international adoption, three by domestic adoption, all by love. They began with a calendar and a plan and ended with a family and a story. The house was packed, and the journey was longer, harder, and more beautiful than they imagined.