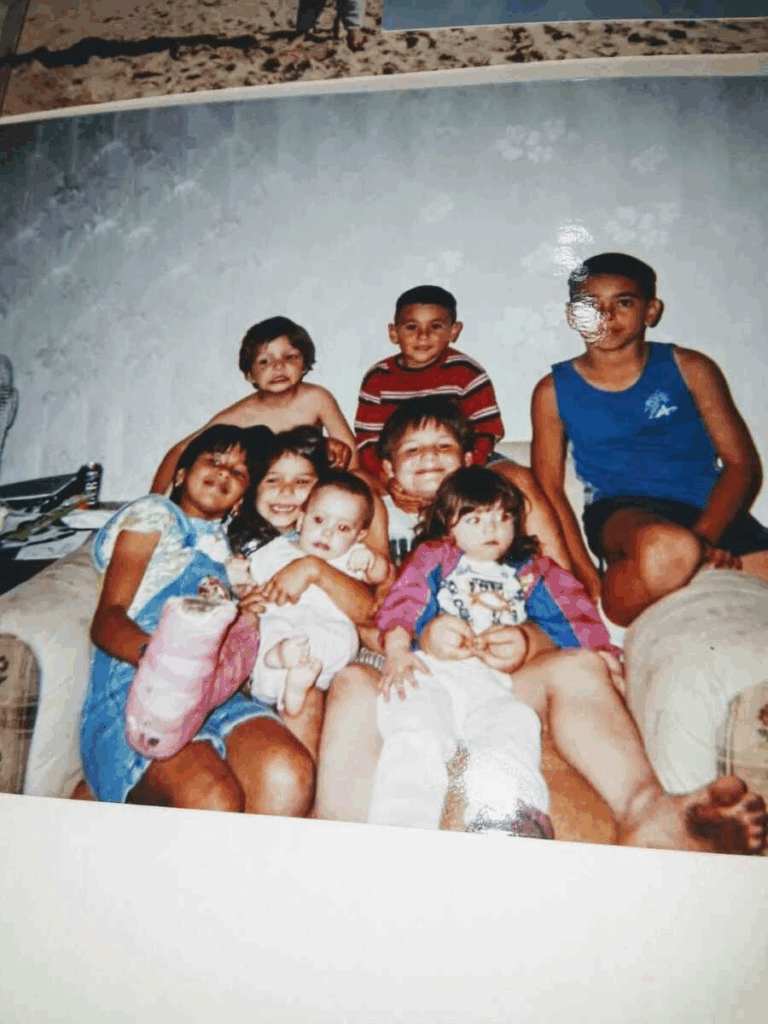

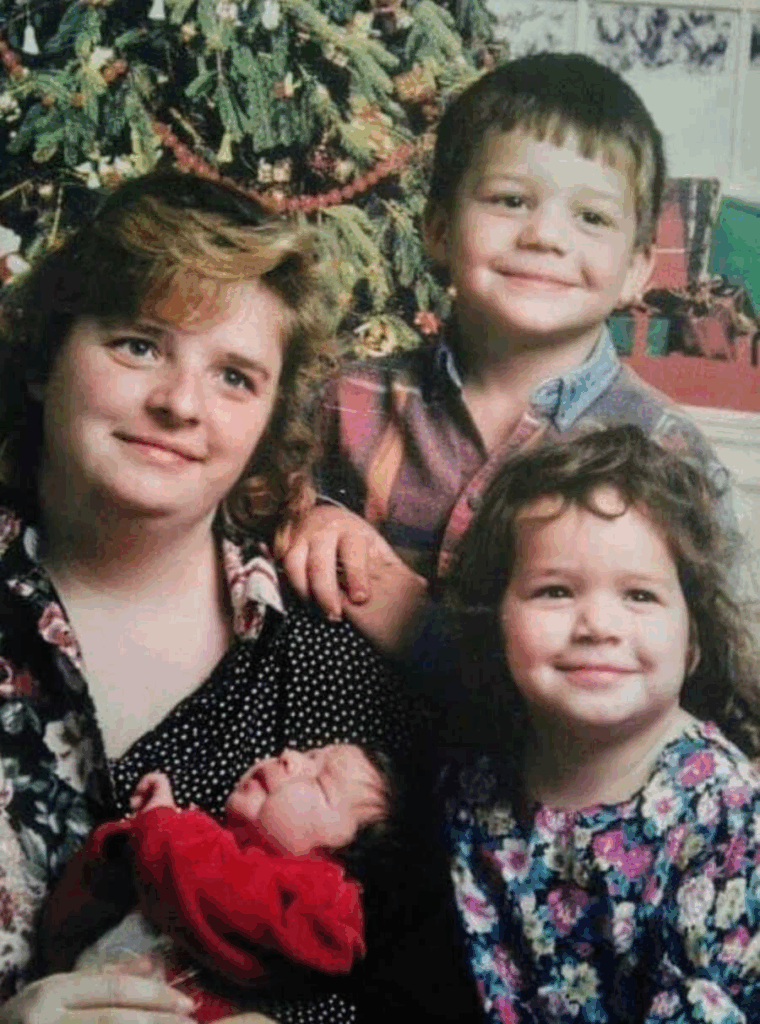

She stays because love steadies her, and she will keep going one determined step at a time with that love. She has been unwell for as long as she can remember. At six weeks old, she survived meningitis after doctors warned her parents she might not make it. Childhood did not settle into calm. Her feet curved inward, she struggled to walk straight, and at seven, she had surgery with a metal pin and a cast, then a wheelchair and a walker while she learned to walk again. Neighbors and classmates were kind, pushing her chair and pulling her out of danger once when it got stuck in the road. As soon as she could, she ran toward life. She played softball, tried cheerleading, and even carried her toddler brother from a house fire. She was sure she would never need that wheelchair again.

At eleven, a new battle arrived. Crushing cramps and heavy bleeding left her anemic and bedridden. Doctors first guessed gastritis, then diagnosed endometriosis, later adenomyosis, and fibroids. She tried birth control, Lupron, and a D&C. Anxiety and depression followed. At fourteen, she was in a car crash that left her with facial stitches, but she bounced back. She kept her grades with a 504 plan for flare days and tried to stay bright and busy.

On Halloween 2010, after hours of walking, her feet swelled so badly her boyfriend had to carry her home. By morning her legs were purple and she could not stand. In the emergency room a tick bite was found and doctors suspected Lyme disease, warning arthritis might come later. The swelling eased and she walked out, promising herself she would keep moving. She married, had two high risk pregnancies, and two boys. One was born at 35 weeks; the other lost oxygen at birth and has cerebral palsy. An obstetrician told her Lyme would have shown on tests and blamed her foot pain on arthritis and plantar fasciitis. She became a single mother, worked hard, and kept going.

In 2015 she met the man who would become her husband. Life felt full again. A foot specialist found a genetic ankle issue and arthritis. Insoles helped. She and her husband tried for more children. There was a miscarriage, then two more pregnancies with an incompetent cervix and severe hyperemesis. She had PICC lines, gave herself medication three times a day, and delivered early but healthy babies. The last pregnancy brought a subchorionic hematoma so large she was urged to end it. She went on bed rest and made it to 35 weeks. After birth she developed a uterine infection and sepsis and was hospitalized while her baby stayed in the NICU.

Two months later, in April 2019, she had a tubal ligation. Three days later, the world began to tilt. She woke dizzy, swaying as if on a boat, too fatigued to stand. ER tests came back normal. She was told it might be dehydration or anemia and sent home with vertigo pills. Nothing helped. Hoping to stop the bleeding that worsened her anemia, she had a hysterectomy at 27. The dizziness stayed. An MRI finally explained part of it: a Chiari malformation, with her cerebellar tonsils dropping into her spinal canal, and a degenerative back problem. The neurologist warned of sleep apnea, vision loss, even death in her sleep without treatment, and raised the prospect of brain decompression surgery.

During the pandemic in June 2020 she had that surgery. She shaved her long curls and went in with hope. The surgeon did not need to open the dura because her brain decompressed on its own. It sounded promising. But due to hospital rules she could not have her husband stay. She panicked, signed herself out against medical advice, and rode home after brain surgery. Weeks and then months passed with no relief. The vertigo and pain remained. Depression deepened until she felt she could not go on. A neurosurgeon offered only fifty percent odds that a second, riskier surgery would help. She began using a walker and sometimes a wheelchair, a return she once swore she would never make.

What kept her here were her children, her husband, and her family. She started therapy, tried new medications, and saw a pain clinic. She was diagnosed with fibromyalgia. Steroid injections did not help, but a nerve pain drug gave her more good days than bad. She is waiting for vestibular migraine injections and still manages dizziness and pain daily. She may need more therapy, more procedures, more tools. She may always lean on rails, walkers, and wheels. But she has learned to measure progress in ordinary moments: reading to her kids, riding in the passenger seat while her husband drives, laughing on a day that does not spin.