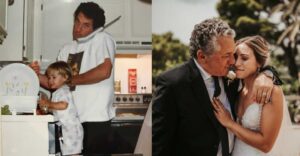

She didn’t wait for the world to define her; she took the bitter with the sweet and wrote herself into the story. She often looks at her life and thinks nothing would have happened without her parents choosing her. Juliana was born in Peru to a teenage mother during a time of violence and fear. Her first mother made a brave choice so her baby could live safely, and Juliana has respected that love for as long as she can remember. She was adopted at a few months old by the people she simply calls her parents.

They were steady and warm; her mother noticed every struggle and fought for every bit of progress. When Juliana barely spoke and even slid out of chairs because her body didn’t reasonably cooperate, her mom found specialists, tools, and encouragement. That care helped her grow, discover art, and fall in love with writing.

Even with a happy childhood, the quiet questions of adoption followed her, especially as a transracial adoptee in a primarily white Connecticut suburb in the ’90s. Do I belong? Am I wanted here? She once drew herself in art class with pale skin and blue eyes, jolting her parents. The family moved to New York City, where differences felt normal. It helped, but identity questions didn’t vanish.

Middle school brought bullying, and high school brought a trauma she still carries. Anger replaced lightness. She dated a boy who became her first love, and for years, they were messily on and off, fighting, breaking up, and finding each other again until the pandemic slowed life enough for them to choose each other for real and build something healthy. Juliana poured her darkness into stories, horror movies, goth aesthetics, and sketches to keep herself from self-destruction.

Her parents worried, but they understood: this was safer than hurting herself, and there were boundaries. On a trip to New Hampshire in 2005, a historically messy but emotionally electric Revolutionary War film lit a spark. In January 2006, she started the project defining her creative life: The Sinner’s Bible.

It was part horror, romance, drama, and high fantasy, an alternate history that leapt from 2006 New York to 1770s South Carolina. Its heart was an adoptee heroine, Juliana “Juli” Katherine Serenade—a troubled goth heiress with a hidden wound, shadowed by a vengeful god-entity, Arianith Lilith Macabre. A twist in fate sends Juli to a small Carolina town on the edge of revolution, where two brothers find her and a wild, tender, violent story begins. The series follows identity, mental health, war, death, worship, and what it costs a sixteen-year-old to be treated like a god.

The work found an online audience, first on Angelfire, then DeviantART, then Instagram, and later grew toward a third edition on Patreon. Along the way, Juliana noticed what was missing in media: real adoptee representation, especially in young adult stories that weren’t only about trauma. Too often, the books focused on pain were written by non-adoptees or erased BIPOC adoptees altogether. Where were the fantasy leads, the superheroes, and the adventures with adoptees at the center? She decided to build what she couldn’t find and make Juli a mirror and a beacon.

Life wasn’t a straight line. In 2013, after friendship fallouts and relationship strain, depression took hold. She moved from New York to Illinois, closer to her extended family. Her aunt, uncle, and cousins steadied her; she rebuilt a kinder circle and started again. A scare in 2018 almost knocked her back, but she kept going. By 2021, still in the pandemic, grounded by a stronger relationship and a stable job, she returned to The Sinner’s Bible, determined to craft its final, best form and bring it to a broader audience. She writes for adoptees, yes, but also for anyone who’s ever felt like an outsider.

Her family mantra, handed down by her great-grandmother, grandmother, and mother, guides her: take the bitter with the sweet. She knows there will be days that test her and days that lift her. She wouldn’t trade the path that gave her parents who chose her, a father who became a best friend, a partner who grew up with her, and readers who say, “Finally, someone wrote us into the adventure.”