I was just six when my parents sat me down and told me I was adopted.. Bedtime was usually ordinary, but this night was different. My father stood at the head of my bed while my mother lingered at the foot. He rarely came into my room, and the air felt heavy, serious. I fiddled with my doll, trying to hide my embarrassment, while he explained that I had been “saved from an accident” and that no one else had survived. They told me I was chosen, a gift to them because they could not have children of their own. I didn’t fully understand the words, but I felt something shift inside me. It wasn’t framed in terms of “family,” “siblings,” or “loss.” It was more like a story, almost a fable. Still, it planted a seed of doubt in my young mind. From that moment on, I began to quietly question who I really was and where I had come from. As I grew I was keep looking to my family where I cane from.

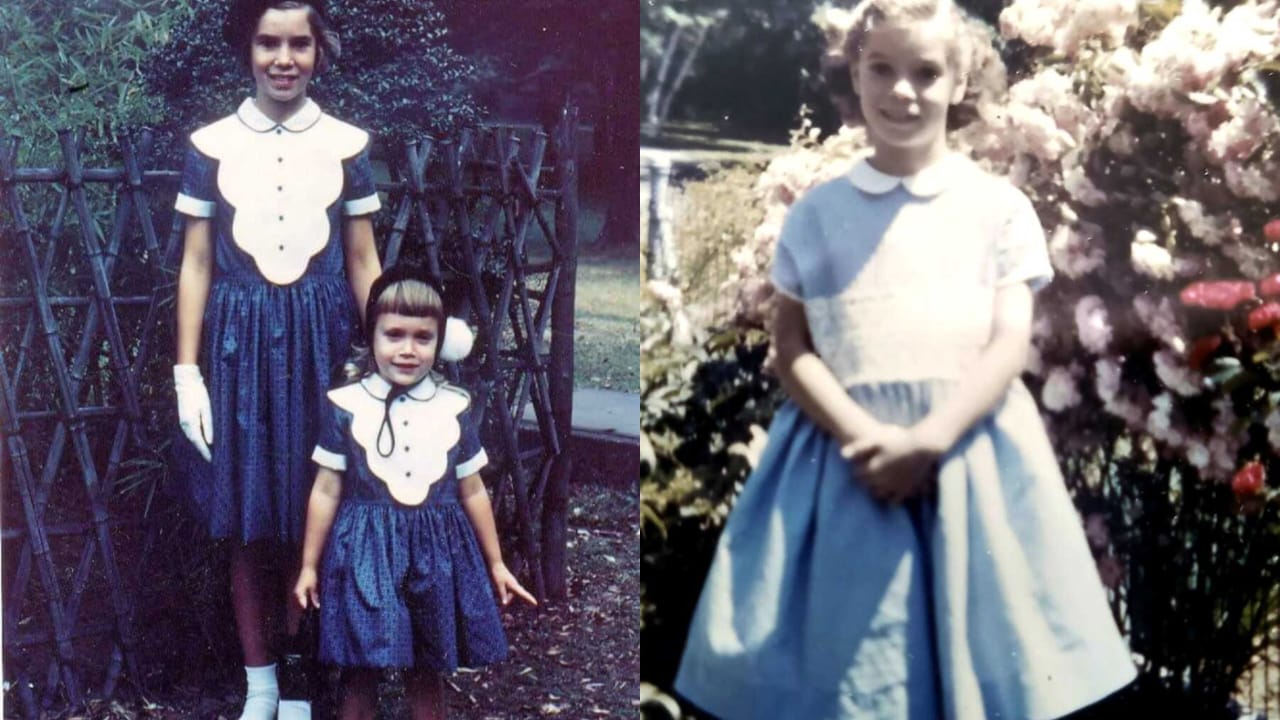

As I grew older, adoption became both a label and a mystery. Within my extended adoptive family, it seemed to give me a kind of special status, as though being adopted made me different, perhaps even set apart. But that difference carried a weight. I noticed how no one in my family looked like me. I didn’t have any genetic reflections to remind me that I truly fit in. I would catch myself wondering, Who am I like? Where are the others? My parents never encouraged those thoughts, but they haunted me all the same. When my parents later adopted a fair-haired baby girl through the same Catholic agency, I adored her, but it reminded me again that my identity was borrowed, pieced together from someone else’s choices.

My dad being in the Air Force just added another layer of complication. His authoritarian style and frequent absences created a home that was often filled with tension. Because of his demanding job, vacations were rare, and my education suffered from constant moves. Each school change disrupted friendships, making me feel even more like an outsider. At times, he would remind me that my behavior reflected on his career, which only deepened my sense that I was somehow inadequate or flawed. I longed for consistency, and I found it only at my grandparents’ home in New Jersey, where my Nana became my anchor. Those years offered me stability I didn’t have anywhere else, and her presence helped shape the few warm memories I still hold from my childhood. Her love give me stability I always searching for.

Despite the appearance of normalcy, adoption was a subject my family avoided. Questions about my origins were shut down, and even when I struggled emotionally, therapy never touched the subject. When people asked if I wanted to know my biological parents, I would automatically say no, as though loyalty to my adoptive family required denial. In reality, I felt an unspoken pull toward my birth mother and wondered if I had siblings out in the world. The thought was both troubling and strangely comforting, but I carried it silently.

Becoming a young mother at twenty brought those feelings to the surface in a way I could no longer ignore. Looking into my daughter’s face, I felt the joy of seeing someone genetically connected to me for the very first time. She was the first person I could really call my own, and that feeling hit me harder than I ever imagined. Yet, it also reopened the confusion I had pushed down for years. How could I feel whole when a part of my story remained locked away?

The barriers to uncovering the truth of my origins were staggering. In my early forties, I discovered that my birth certificate had been sealed by the state of South Carolina. The document I had always known was, in fact, falsified to list my adoptive parents as my biological ones. For years, I lived with an amended identity, unable to access the most basic information about myself. Only after persistent effort and with the help of adoptee advocates was I able to obtain non-identifying information from Catholic Charities. In 1993, after decades of uncertainty, I finally met my birth mother and two half-sisters in South Carolina.

Through that search, I came to understand the broader injustice facing adoptees. Many of us are denied access to our original birth certificates, our true histories sealed away by laws that prioritize secrecy over identity. DNA testing, which wasn’t available when I began my search, has since given many adoptees the chance to reconnect with their biological families. For me, it confirmed my paternal lineage and allowed me to piece together long-missing parts of my identity.

Coming to terms with adoption meant acknowledging the trauma it carries. Books like The Primal Wound helped me understand that the panic, anxiety, and sudden feelings of abandonment I had experienced since childhood were not random they were rooted in the rupture of being separated from my first mother. Even in the best of circumstances, adoption leaves an imprint of loss. That realization gave me language for the grief I had felt for so long but never fully understood.

Now, as an older adoptee, I believe honesty and empathy are essential for adoptive families. Children deserve transparency, not sugar-coated stories of being “saved” or treated as gifts. Gratitude should never be demanded of an adoptee; what we need is space to question, to grieve, and to build an identity that includes all parts of our story. For adoptees, I urge seeking help from adoption-informed therapists and connecting with others who share this journey. The path can be painful, but it is also a way to reclaim what was lost. Above all, I want adoptees to know they are not alone, and that their right to know their origins is a fundamental part of who they are.