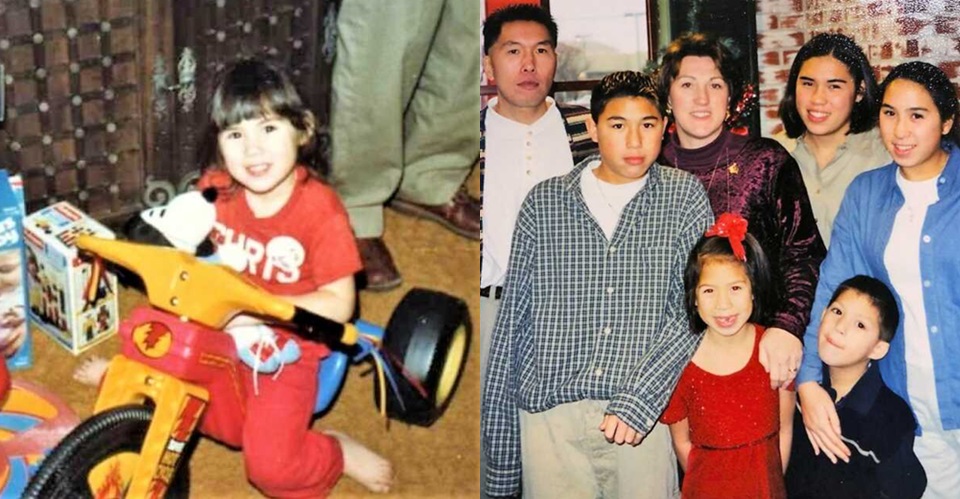

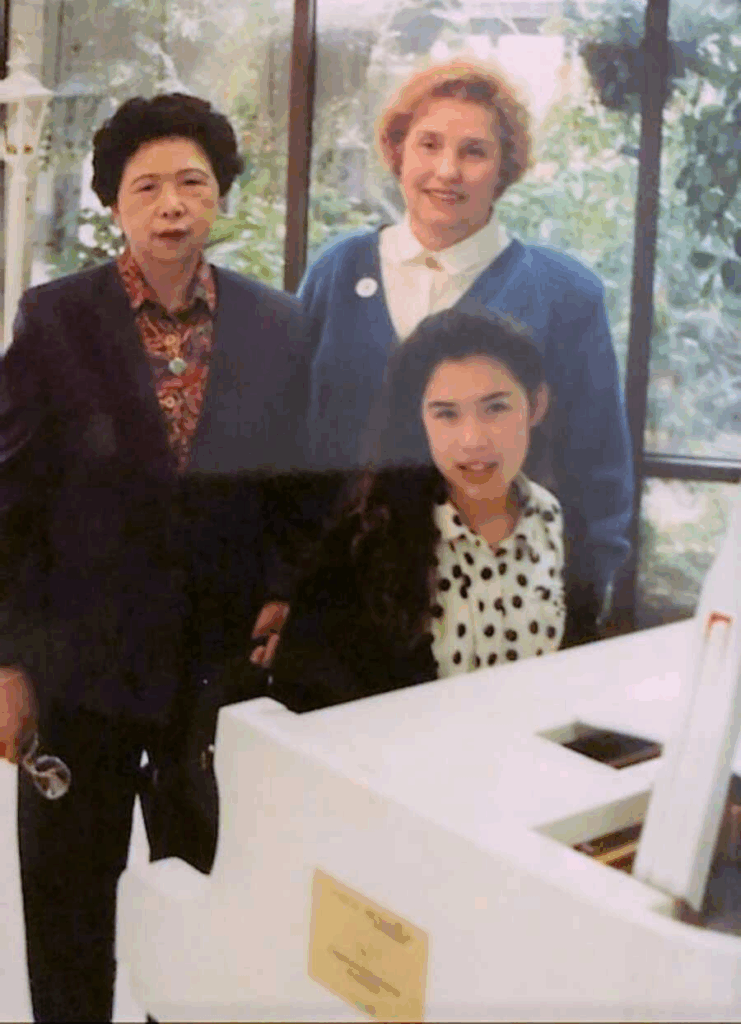

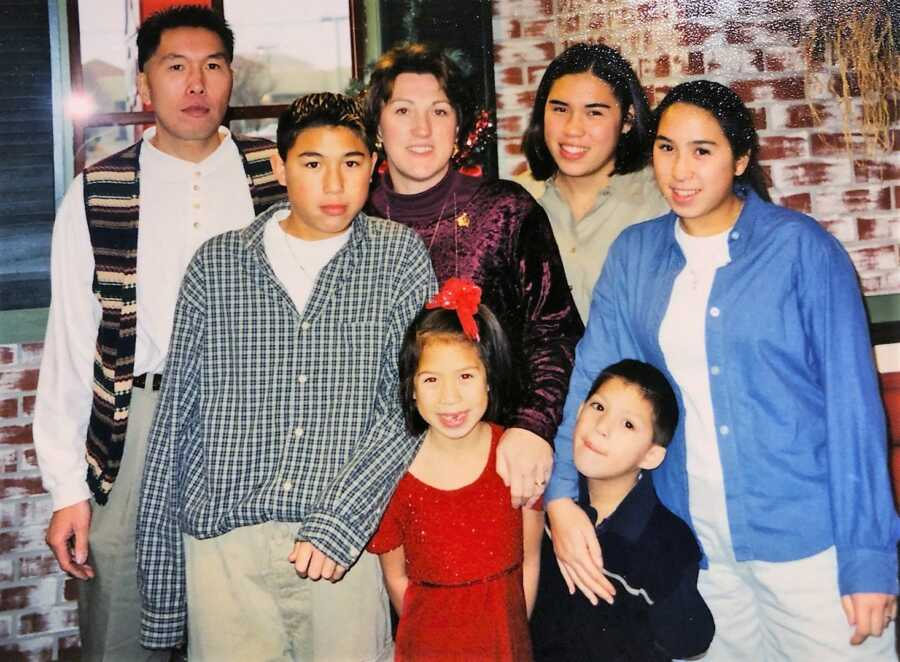

She believes Turning Red isn’t a threat to values; it’s an invitation to laugh, listen, and make more room at the table for stories that aren’t your own. She has what some might call an unpopular take on Disney/Pixar’s Turning Red, but it’s a response to the outrage around it. As an Asian American, I feel the film is familiar in ways many critics might miss. The family’s background mirrors her own; her relatives live in the city, and the early 2000s setting lines up with her teenage years. Even her kids, who are part Chinese, saw themselves in it. If a movie like this had existed when she was young, she would’ve been thrilled to see a main character who looked like her and wrestled with the same cultural currents.

The world of 2002 in the film, before every kid had a phone, when nerds weren’t yet cool, and boy bands still ruled, brought back middle-school memories: a mixed group of friends, a little nerdy, crushing on pop stars, sharing snacks and secrets. Watching it as a parent, she also noticed how her upbringing shapes her parenting, the helpful parts, and the parts she’s working to unlearn. She’s seen the critiques: “too mature,” “inappropriate,” “spiritual content.”

To her, those complaints often come from a narrow slice of culture. Yes, there are puberty-ish jokes and awkward tween moments; they either float past younger kids or spark good conversations. The deeper story isn’t about a period but the weight of family expectations, inherited shame, and learning to be yourself without losing where you came from. It’s about mothers and daughters, love and pressure, and choosing to break patterns that don’t fit.

Some objections singled out the ancestor rituals. That hit a nerve. She remembers honoring her immigrant grandfather by bowing at his grave, an act of respect, not “evil.” In Christian homeschool groups she once belonged to, she now sees how disapproval can slide into something else: the idea that if a tradition isn’t yours, it must be wrong. She wonders if those quick judgments carry a quiet strand of racism, even when unintentional. Why does seeing another culture’s practices make a story dangerous? If a ceremony on screen offends you, maybe pause and ask if it’s unfamiliarity, not immorality, doing the talking. You can name your discomfort, learn something new, and still hold your beliefs.

For her, the movie worked on two levels. It made her laugh with its 2002 nostalgia and tear up because she recognized both the daughter and the mom. It gave her kids a mirror and offered others a window. It doesn’t preach; it invites. And it’s honest about how messy it can be to grow up between cultures, how love can show up as rules, how boundaries can protect or confine, and how choosing yourself can still honor your family. She isn’t saying it’s perfect for every age at every moment.

She is saying it’s a chance: a chance to talk about bodies, boundaries, crushes, friendship, family pressure, faith, and cultural respect. It’s also a reminder that kids’ movies aren’t just for kids; they help parents see their own patterns and decide which ones to pass down. Her verdict is simple: she liked it. It felt real. It felt kind. It felt like home. And if it gives non-Asian viewers a peek that grows empathy, all the better. Stories don’t have to match your life to matter; they can stretch it.

It also reminded her how powerful storytelling can be when it reflects lives that don’t often get center stage. For her, Turning Red wasn’t just a movie about a teenager turning into a giant red panda; it was about identity, cultural connection, and the tension between fitting in and standing out. Stories like this matter because they validate kids who rarely see themselves on screen and challenge others to recognize that different doesn’t mean wrong.