The magic of Santa is brightest when every child can see themselves in it. On a stormy summer night in 2019, a woman said yes to welcoming a nine-month-old baby girl into her home. She knew almost nothing: no family history, medical background, or even the child’s skin tone. Yet when she held the baby for the first time, something clear and steady formed inside her: a new purpose.

If she were going to love this child well, she would learn about African American culture. She set out to understand hair care and skin health, find “racial mirrors” so her daughter could see herself reflected in the world, and weave their two lives into one loving, whole family. The questions and plans came like waves, but her commitment never wavered.

That promise changed her life over the next three and a half years. She had always believed fostering a child means fostering their whole family and story. To her, the most respectful way to support a family of a different race is to honor their culture with care and consistency. She worked to affirm her daughter’s black identity daily, not by pushing back against social norms with anger, but by lifting what is beautiful, strong, and accurate about black culture.

She wanted her daughter to grow with confidence and joy, meeting life’s barriers with grace, dignity, and pride. She realized that to raise an emotionally secure black child, you first have to know and celebrate what is wonderful about being black. The holidays brought that lesson into sharper focus. Many people picture Christmas through a familiar lens: rolling out sugar cookies with Mom, tossing reindeer food on the lawn, and bundling up to play in the snow with Dad. For many families,” Santa” automatically means an older white man with a fluffy beard and a big laugh.

But she believed that Santa should reflect the child waiting for him. The magic could fit the child’s identity, not vice versa. It’s a simple idea that has caused controversy for generations. Why does a Santa of color bother some people? Part of the answer, she thinks, is history: lining up to sit on Santa’s lap became a ritual tied to a particular, post-war, middle-class white experience.

When that image shifts, some people feel their place in the story is threatened. But it doesn’t have to be a threat at all. Instead of saying, “ There’s nothing wrong with being white,” perhaps it’s time more people said, “ There’s nothing wrong with being black.” The heart of Christmas isn’t about choosing sides; it’s about love, generosity, and joy shared freely.

Children of color live in a world where race can make everyday life harder in big and small ways. Christmas should be a break from those burdens, a season where the wonder of the holiday is presented in their image, not someone else’s. Her daughter was black, and she was white, but that reality doesn’t dilute her child’s identity or heritage.

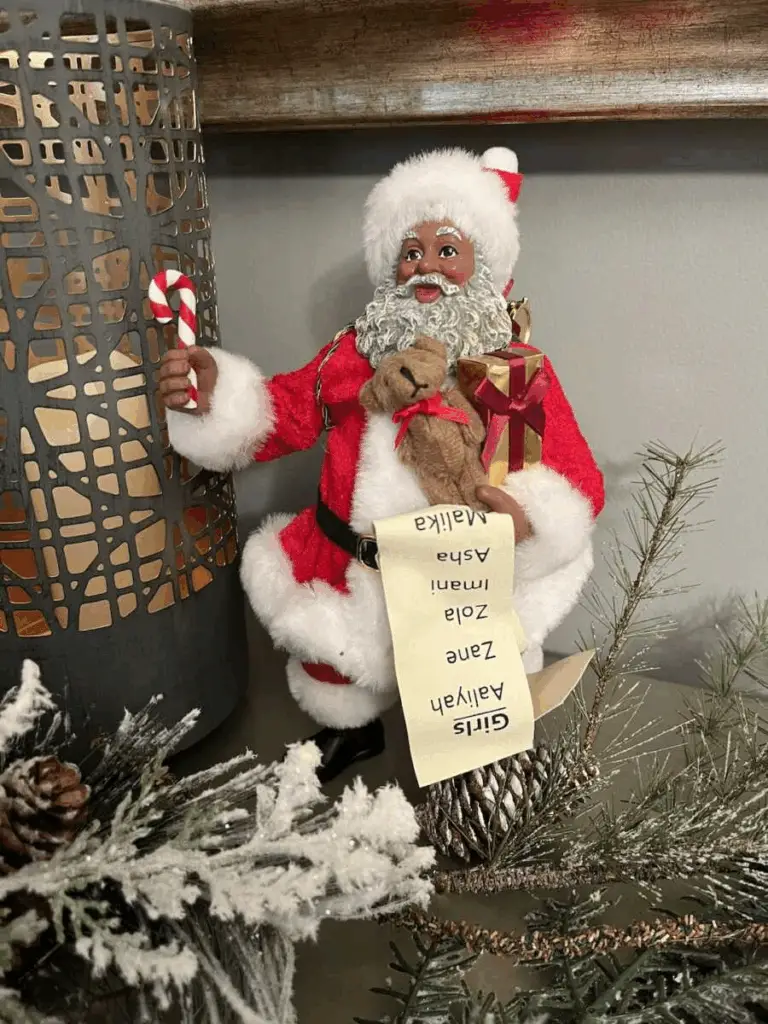

If anything, it demands more intention. Belonging is not automatic; it’s built, so she filled her home with black Santas, on the mantle, in storybooks, on ornaments and figurines, so that each December her daughter sees a jolly figure who looks like her, loves like her family loves her, and stands for a joy that includes her without question. For this mother, that’s the whole point: Santa isn’t supposed to mirror one version of America or one kind of childhood. Santa is the symbol of seasonal love that belongs to every family and every child, and with no doubt, everyone deserves this kind of joy in life.