Nora doesn’t need fixing, our world does; so they choose love, access, and inclusion, one appointment, one playground, one brave conversation at a time. She was 26 weeks along when a doctor quietly said, “Your baby isn’t growing as expected.” Sitting alone in Maternal Fetal Medicine, she felt the floor tilt. Until then, every scan had looked good. Because of age and high blood pressure, she’d been closely watched, but the baby, so far, seemed fine. The measurements told a different story: the long bones in her daughter’s arms and legs were behind.

The words “skeletal dysplasia” entered the room and wouldn’t leave. There weren’t many answers. “Most likely achondroplasia,” the doctor said, “but we can’t be sure without more tests.” She declined invasive testing; results might arrive too close to delivery to change anything. An MRI gave more explicit pictures but no certainty, just more “wait and see.” So they waited. They monitored. They googled too much. They worried for eleven long weeks.

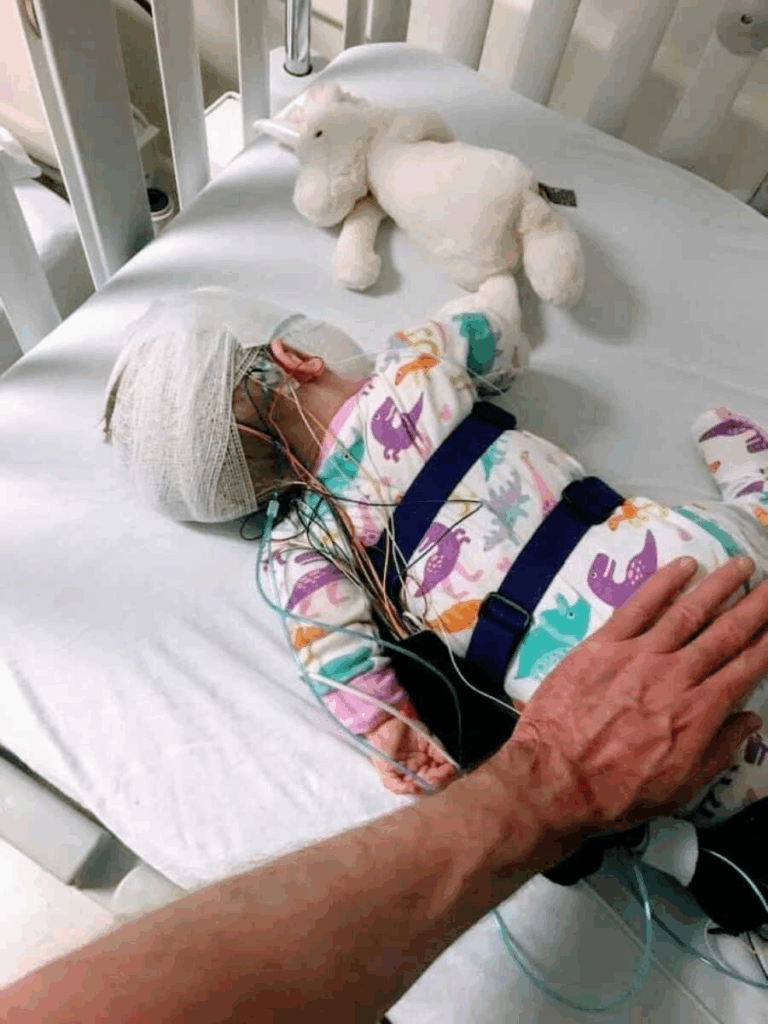

At 37 weeks, her body said, “Enough.” They moved to a hospital with a NICU and a larger team in case their daughter struggled to breathe; her chest looked small on scans. After hours of fluids, rising blood pressure, and a haze of exhaustion, their little girl arrived crying. That tiny cry was everything. She could breathe. They could exhale. A doctor called out, “It’s what we thought.” The baby, soon named Nora, was whisked away for checks. Other than low blood sugar, she was stable.

In those early days, Nora showed many features of achondroplasia. Specialists came and went, orders stacked up, and information poured in faster than it could be absorbed. She missed her older son, Nate, and felt like a first-time mom again, except the rules had changed. At home, Nate met his sister “sissy,” he declared, and adored her immediately. To him, she was tiny toes, soft cheeks, and perfect lips. When mom later explained Nora would be a little person, he thought it meant she’d stay a baby forever. They talked, they questioned, they loved her just the same.

The appointments multiplied: orthopedics, neurosurgery, ENT, genetics, sleep studies, X-rays, MRIs, car seat tests, and on and on. Five months later, genetic results arrived and confirmed what everyone suspected: achondroplasia. Having a name helped them plan. They learned the practical stuff quickly. Nora had severe hypotonia, “floppy” muscles, so that milestones might come later: sitting, crawling, walking. Her head is proportionately larger, and with weak neck and back muscles, they had to protect her spine.

No swings, rockers, slings, or specific seats at first; lots of flat-surface time and gentle floor play; careful, steady tummy time as she grew stronger. They heard about risks common in achondroplasia, bowed legs, curved spines, crowding in the mouth and nose, sleep apnea, hydrocephalus, ear infections that can affect hearing, foramen magnum compression that sometimes requires surgery, plus a higher SIDS risk. It was a lot for any parent to hold.

She also learned what many people don’t see: being small in a world built for average height is only part of it. There are medical hurdles, but there are social wounds, too, including stares, jokes, bullying, and exclusion. She decided early that Nora doesn’t need to change; the world does. Accessibility, respect, and inclusion aren’t extras; they’re essentials. Some days felt like they’d been robbed of the newborn season, so many unknowns and fear. And then she found other parents of little people (POLP). They understood: the late-night worries, the paperwork pile, the joy of small wins, the ache of what-ifs. Their community became a lighthouse. Later, she began guiding newer families, reminding them that shock can soften and joy returns.

Nora is four, curious, funny, and determined. She plays soccer in a pink tee, zips along on a scooter in her bright helmet, and picks flowers with fierce concentration. Appointments still happen, but life has a rhythm. There are slower stretches, deeper breaths, and a confidence they didn’t have at the start. Watching Nora look up to her big brother like he hung the stars is still sweet. If you take one thing from their story, let it be this: kindness. Celebrate differences.

Believe disabled lives are whole lives. Build spaces that include everyone. Speak up when you hear jokes or see barriers. Meet each person as a person, not a diagnosis. That’s how the world gets better.