Andrea couldn’t choose her pain, so she chose her purpose and turned “maybe someday” into help for others. She grew up learning to live with pain. By middle school, she had her first period: by junior high, she was already in the hospital for pelvic pain; by high school, she was using pain pills just to get through the days.

Years blurred into a cycle of scans, ER trips, and bursting cysts. At 21, a college senior, she finally thought answers were coming. A surgery was scheduled, then suddenly canceled. One doctor said “hernia,” another had seen a cyst, and none of them matched the pain she felt on the opposite side. She held it together until she reached her car, called her dad, and cried that she wasn’t making it up; something was wrong.

A referral changed everything. After a long wait list and a favor called in, she sat on an exam bed while Dr. Paige Partridge performed the ultrasound herself. On the screen was a seven-centimeter ovarian cyst, about the size of a grapefruit. It wasn’t “nothing,” it was real. Surgery happened the next day. The relief was immediate, and the diagnosis of endometriosis finally matched the life she’d been living. Looking back, the clues were there. As a young teen, over-the-counter meds never touched her cramps. Bleeding went on for more than a week at a time. In high school, every hospital visit followed the same script: pelvic pain, scan, ruptured cyst, discharge with narcotics.

She was the one who first suspected endometriosis and raised it with a doctor, who tried birth control but never pushed for surgery. The medication dulled the edge, but the mental toll of an invisible illness piled up. One boyfriend made her weight a condition of love; the pills numbed more than just the cramps.

That first surgery brought a window of calm. She graduated, started dating the man who would become her husband, and moved to Dallas. The pain returned, but she avoided falling back into painkillers. In 2010, they married. By late 2011, she was trying to conceive, and in 2012, she saw the two lines she feared she might never see.

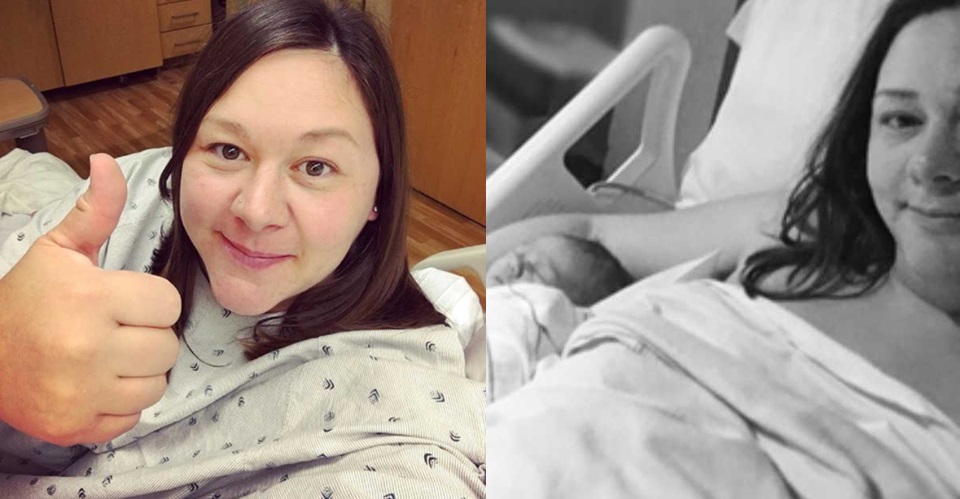

A son was born in 2013, and a daughter was born in April 2014. Two C-sections later, doctors warned her to wait before another pregnancy. For a while, the pelvic pain quieted. In 2016, it roared back; a new doctor confirmed endometriosis was still growing. Surgeries followed, one in 2016, one in 2017, and two more in 2018, after a move to Tulsa. She even tried Lupron, a drug many patients avoid, because she was desperate. It didn’t help; surgery removed another cyst and revealed lesions on her bladder. A hysterectomy was advised. She wasn’t ready; she and her husband hoped for a third child. She stopped medications that weren’t pregnancy-safe and tried naturally, while ultrasounds kept showing inflamed tubes.

Another cyst grew; by December, she needed another operation, and her doctor warned that without removing her ovaries, the cysts would keep coming. In early 2019, standing in a Disney World line, she scheduled the hysterectomy she had fought to avoid. Friends and family wrapped her in support. Pathology explained the heartbreak: her fallopian tubes were full of endometriosis, which likely caused the inflammation and blocked the path to a third baby. She was grateful for her two children and the timing that made them possible, even as she grieved what wouldn’t be.

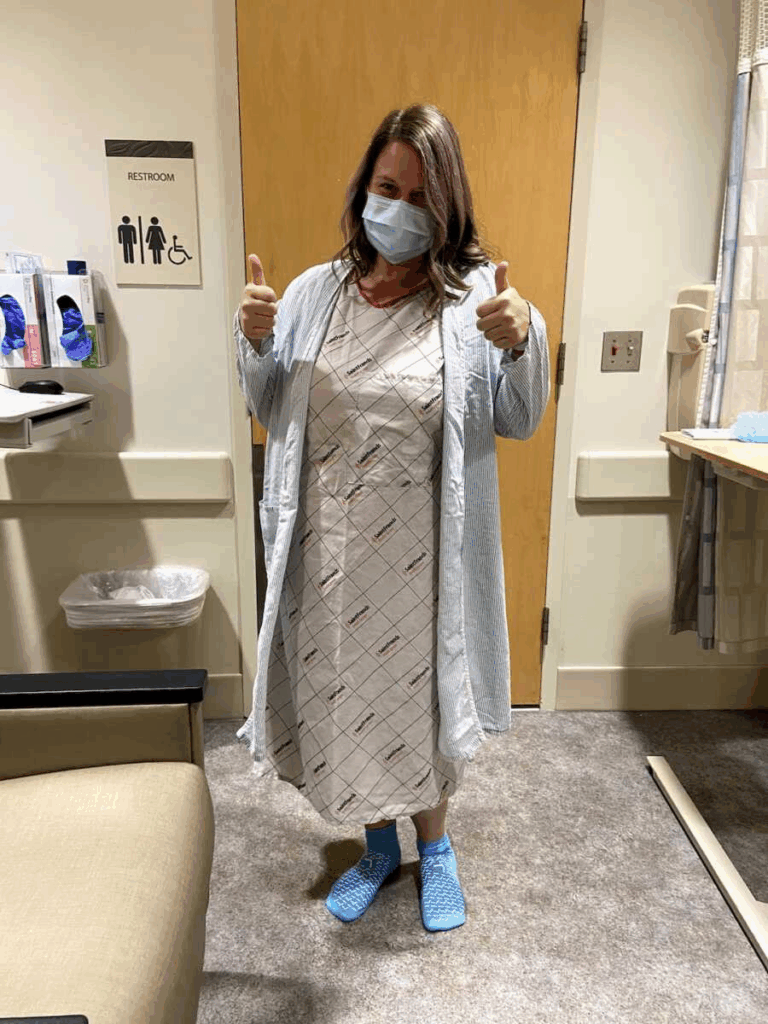

The journey didn’t stop with the hysterectomy. In 2020, another surgery showed disease on her pelvic walls and floor, and again on the bladder. She dealt with interstitial cystitis, bouncing between specialists until she found an excision surgeon through Nancy’s Nook and had surgery in March 2021.

In October 2022, she learned she’d need yet another procedure. Grief and guilt hit hard, over money, time off work, the toll on her family, and the endlessness of it all. She manages what she can: antidepressants, medication for migraines and hormones, supplements, and short-term pain meds only after surgery.

She hopes the subsequent excision will be scheduled soon; it could be the last, knowing she had whispered that hope before. She was channeling her energy into a nonprofit so others with endometriosis can reach skilled care, financial help, and real validation faster than she did. She knows she’s been fortunate to have access to resources and love.

She wants that to be the rule, not the exception, especially for her daughter’s generation, so fewer girls grow up thinking pain this big is “normal.” Her dream for a third child has a new form now: an organization built to protect people like her. The disease took many things, but not her voice, and she plans to use it.