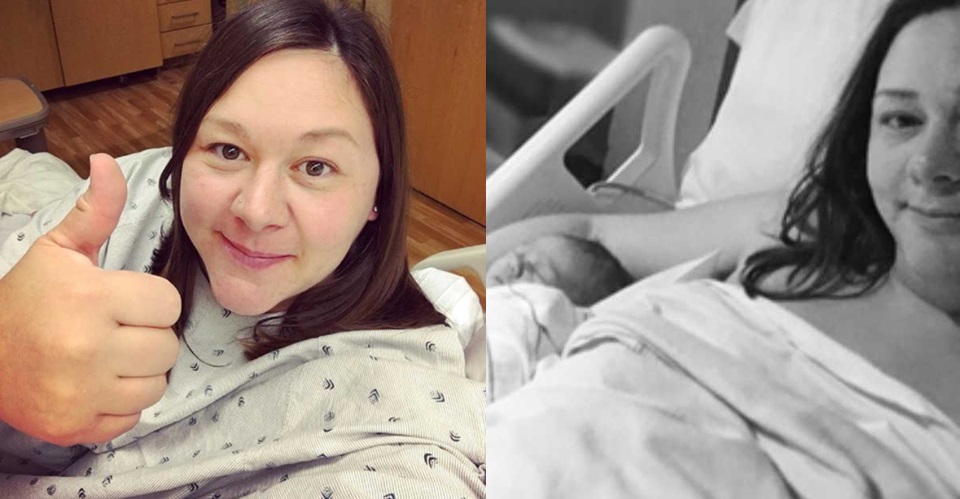

People often say kids won’t let themselves starve. That might be true for many children, but not for my son, Harrison.

When he was six months old, we started him on solid foods. With my two daughters, this stage had been fun and easy. They loved trying new foods and ate just about everything we put in front of them. I thought Harrison would be the same, but he wasn’t interested. We tried rice cereal, then different purees, but he turned away. We figured he was just picky, the way some kids are, and didn’t worry too much. Over the months, we offered him puffs, crackers, tiny bites of fruits and vegetables, beans, cheese, even sweets like cookies and ice cream. He refused it all.

At his one-year checkup, I learned how serious things were. In three months, he had gained only one ounce. He had grown taller but barely put on any weight. He had fallen off the growth chart. His calorie intake simply wasn’t enough to support his body.

I bought cookbooks filled with tricks to hide vegetables in kid-friendly meals. I tried special plates, colorful utensils, and even shows and songs about food. If there was a product made to help picky eaters, I bought it. Still, nothing worked.

Then I noticed something that broke my heart. Harrison would eat chalk, paper, or ice—things that weren’t food at all. This condition, called pica, made me realize it was more than just picky eating. On his first birthday, I gave him a Dr. Seuss book, signed by friends and family, a tradition I did for all my children. One day, he ripped out the pages and ate them. That was when I knew something was truly wrong.

The guilt was crushing. Feeding your child feels like the most basic job as a parent, yet I couldn’t manage it. Sometimes, I let him eat paper because I thought having something in his stomach was better than nothing. I hated myself for it.

When we returned to the pediatrician, Harrison had actually lost weight. The doctor diagnosed him with ARFID Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder. His ribs and shoulder bones were visible, and blood work showed he was malnourished and had very low iron, which explained the pica.

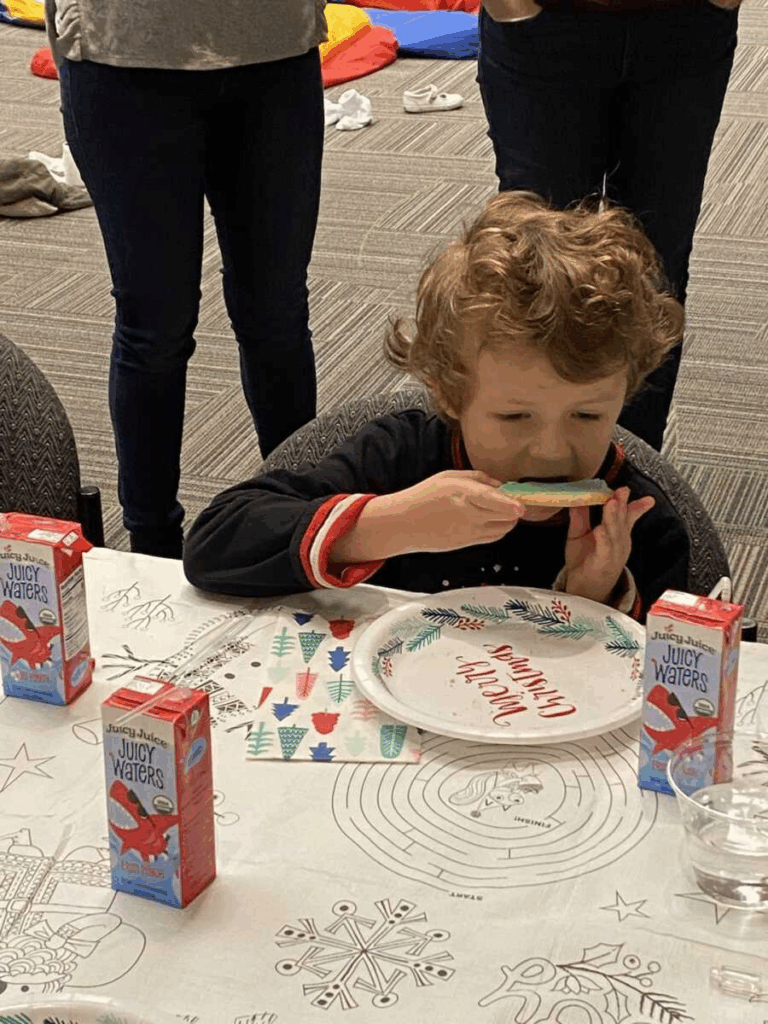

He began feeding therapy through our state’s early intervention program. Every other week, an occupational therapist came to teach us strategies to get him to take pediasure and slowly try new foods. Meanwhile, my friends were taking their children to ballet or story time. I avoided playdates and birthday parties, afraid Harrison would try to eat paper or refuse cake while the other kids ate happily. I felt isolated and robbed of the normal parenting experiences others seemed to enjoy.

After more than a year of therapy with little progress, we were referred to an intensive feeding program at the children’s hospital. There was a long wait, but eventually, we got an evaluation. I felt so much hope, only to be crushed when they told me Harrison wasn’t stable enough to join the program yet. Instead, they recommended a G-tube for nutrition. To me, that felt like failure.

I begged for another option, and the doctors agreed to try monthly iron infusions and pediasure first. For six months, we worked hard, and finally Harrison was stable enough to be put on the waitlist. But just before he could start, he stopped drinking pediasure. His only option now was an NG tube, a smaller tube that went through his nose. It was painful to accept, but I was relieved too. For the first time, I knew he was getting nutrition without a daily fight.

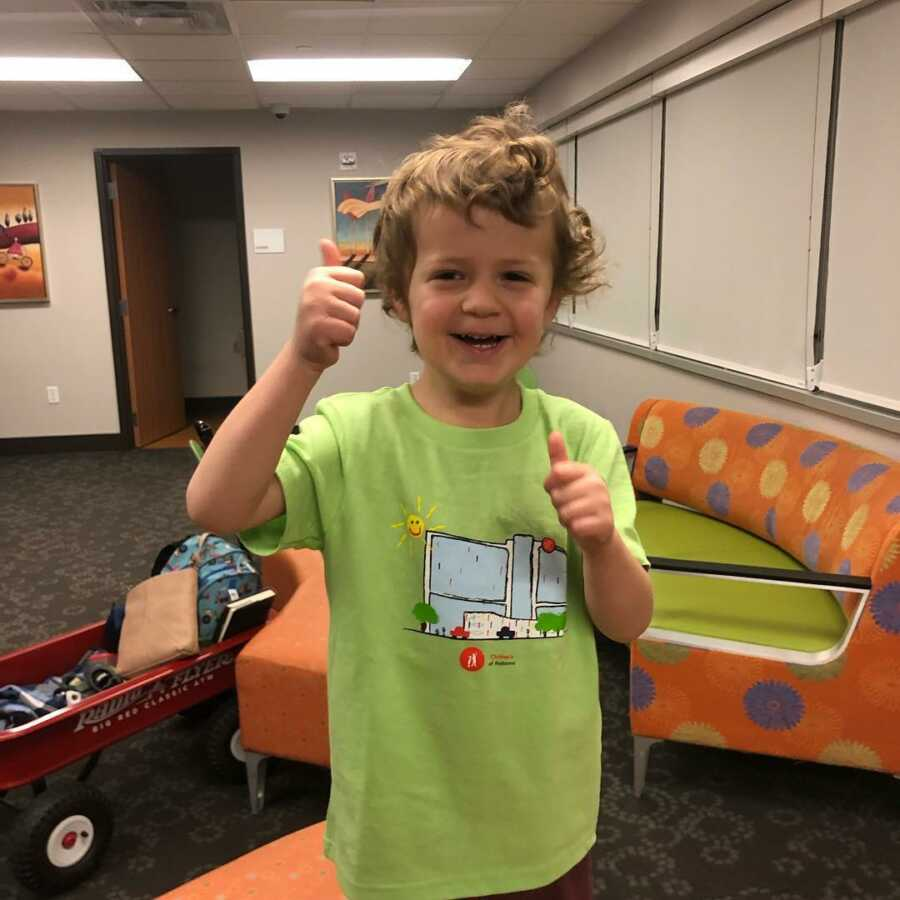

When his spot in the program opened, we began ten weeks of therapy, five days a week. At first, it was awful. He cried, screamed, and refused food. Watching from the observation room, I often wondered if we were doing the right thing. But slowly, he started to accept pediasure, then yogurt, then pureed sweet potatoes. When he graduated, he no longer needed the tube and was stable enough to move forward.

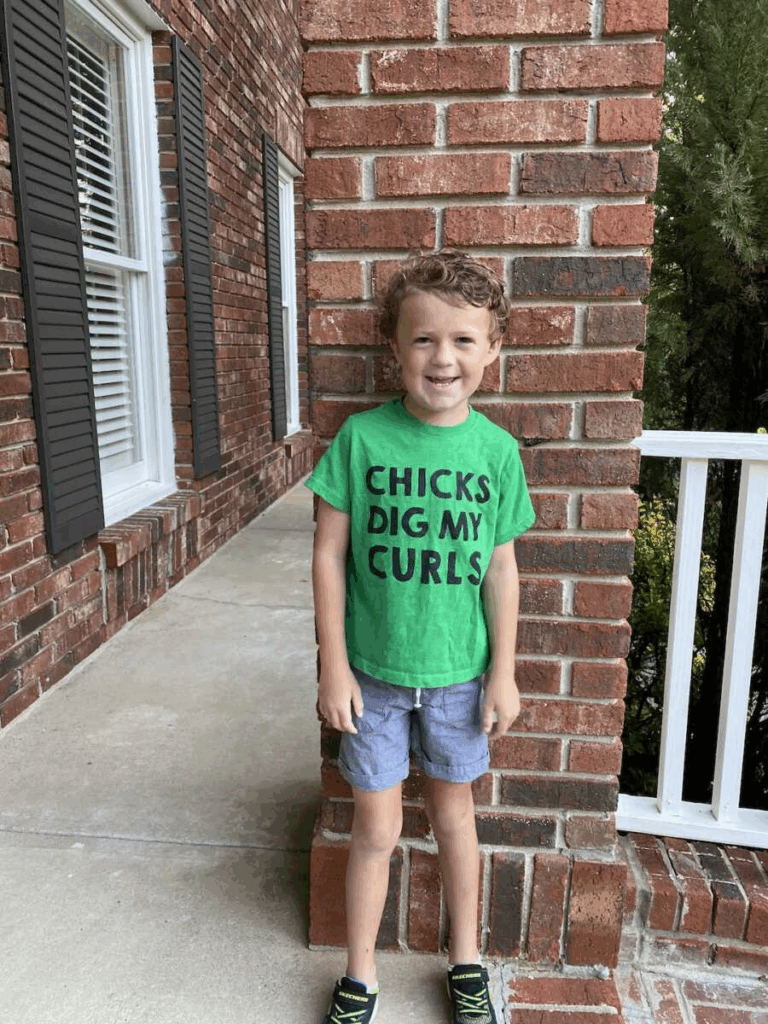

The next year was tough, but we managed to introduce 27 new foods. He still struggles with fruits and vegetables, and mealtimes take extra effort, but he has come such a long way. Today, he drinks pediasure for extra nutrition and requires some support at school meals. I used to see this as him being different, but now I see it as simply what he needs to stay healthy.

Harrison will probably always struggle with eating, but that’s okay. We’ve learned how to support him, and we have a community that helps us when we need it. As one of his therapists once told me, “He isn’t broken. There’s nothing to fix.” Harrison is exactly who he’s meant to be, and he’s worth every ounce of effort.