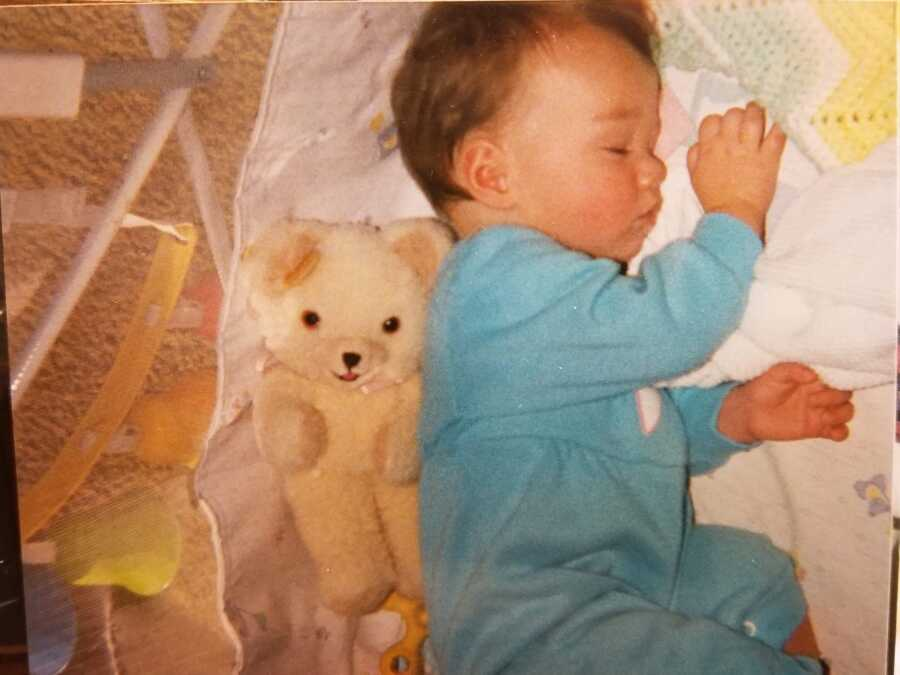

She was handed labels and losses she never chose, but she kept the one that mattered, Hope, and now she’s living up to it by turning pain into a pathway for healing. She lost something before she even knew what loss was. At three days old, just as her mother’s milk came in, she was carried from her mother’s arms to a stranger’s home. The state had already decided her mom couldn’t parent. Her birth certificate said “Keri Hope,” but her first foster parents were told they could rename her; the odds of going back were almost zero. They chose “Theresa Cathleen,” calling her “TC,” and dreamed of adopting her.

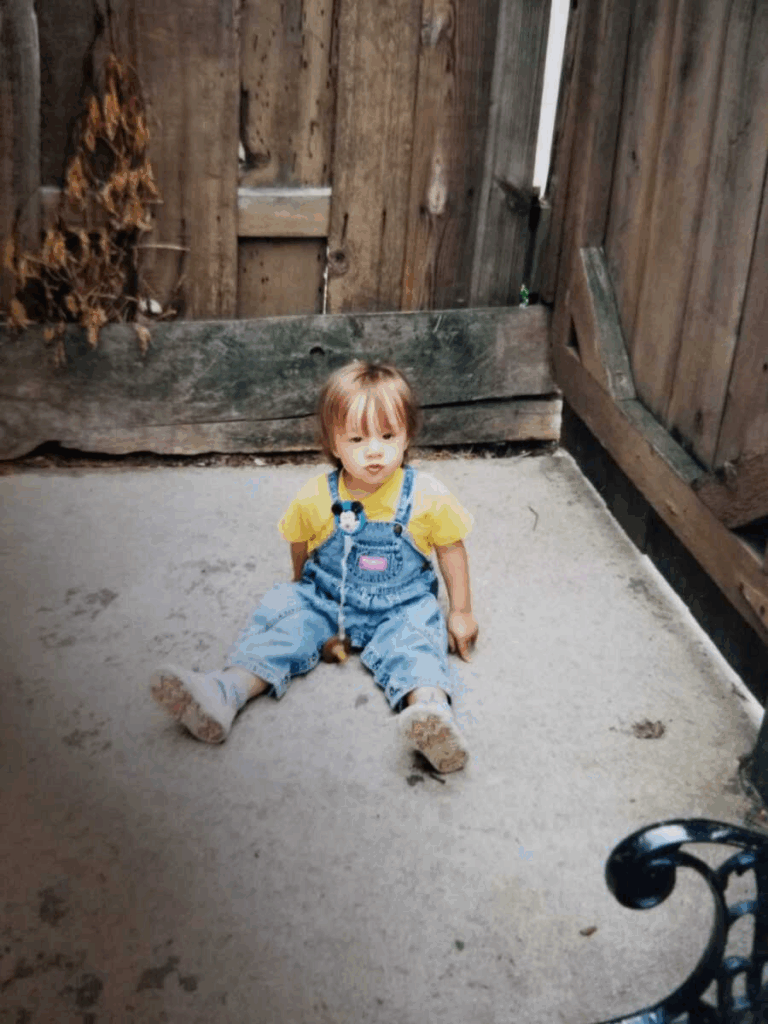

Then everything flipped. Around age two, she was reunified with her biological father. Her foster family was heartbroken; her birth family learned to call her TC because that was the only name she knew. Two years later, the placement proved unsafe. At four, she re-entered foster care and returned to the name Keri Hope. In four short years, she had been removed, renamed, reunited, renamed again, and exposed to instability and harm that no child should face.

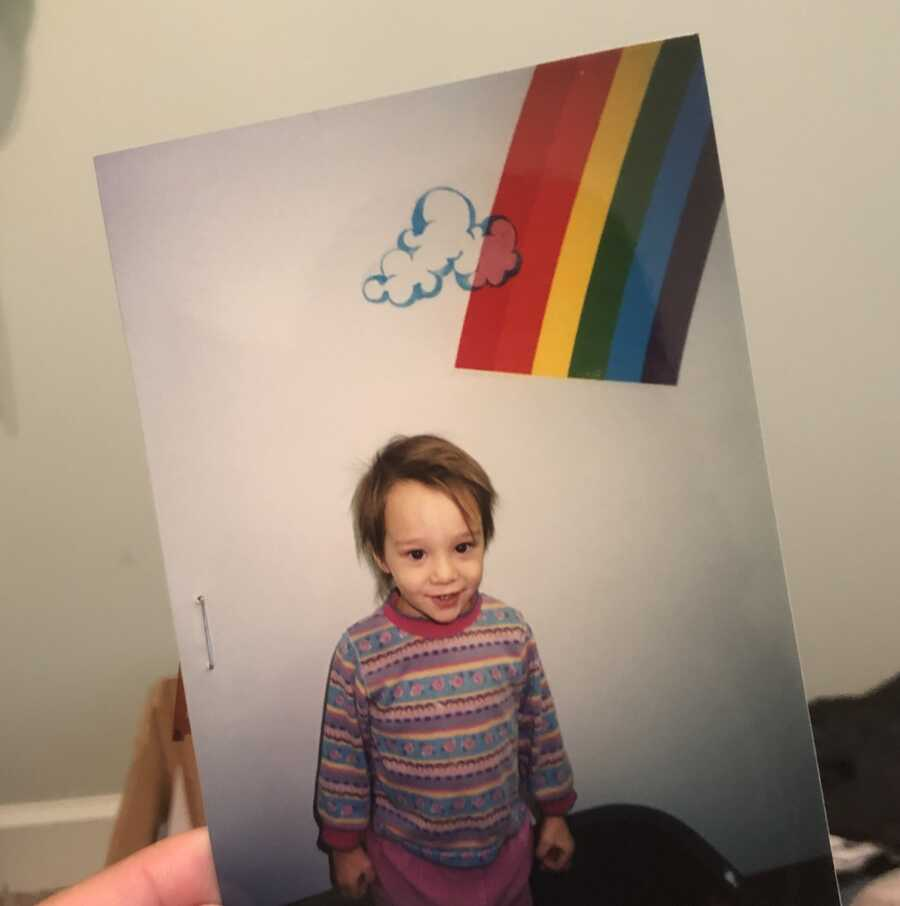

By five, a large family with five children wanted to adopt her. On paper, it looked like a new start. In reality, adoption didn’t deliver a fairy tale. Within two years, her adoptive parents were divorcing, substance use clouded the home, and she learned early lessons that love could leave, adults might fail, and belonging felt like something you had to earn. She coped the way many kids do, by performing. She chased gold stars, joined teams and clubs, and tried to outrun the ache with busy schedules and good grades.

High school was a blur of late shifts, skipped classes, and a deep fear of going home. A lifeline appeared when her best friend’s family opened their door and said, “Stay.” That simple welcome changed her path. College became her way out and her way through. She poured herself into everything: student government, a sorority, campus jobs, even a TEDx talk. She walked the stage as a “success story” from foster care, mentioned by the university president at graduation. It was true and also not the whole truth. Achievement looked like healing, but the old wounds still needed attention.

It took time to understand where she came from and who she was beyond survival. She is the daughter of a mother with a mental health diagnosis. The daughter of a father who lost his own dad young and struggled with alcohol and drugs. The granddaughter of a Filipino woman who fled to America as a single mother after witnessing unspeakable violence in World War II. She carries that history in her bones: she is Filipino, a former foster youth, and someone living with complex PTSD.

When her adoptive mother died, Keri found her foster care file among her belongings, court orders, psychologist notes, and police reports. Reading the record of her childhood from a clinical distance broke her heart and set it free. She grieved the little girl who had been asked to hold too much and began to let go of the lie that any of it had been her fault. Understanding her parents’ own trauma, poverty, immigration, and addiction made space for compassion. It didn’t excuse the harm, but it explained the patterns. She also saw that adoption, like any family story, can carry its own unhealed hurts. Generational pain had run through both families.

So she chose a different inheritance. She is committed to doing the slow work, therapy, honesty, faith, and rest, so she doesn’t pass on what hurt her. She shares her story not for sympathy, but in case it helps someone else lay down their shame and start mending. Along the way, she returned to the name she started with. “Keri Hope” wasn’t just a legal line but a promise. Once, a stranger praying for her at church said, “You are not meant to carry these burdens, you are meant to carry hope.”

It felt like her name answering back. She is 28, steady and determined, building a life marked by courage, love, and service to children and families who stand where she once stood. She knows life isn’t tidy or simple. But she also knows that healing is possible, and that names can be maps home.