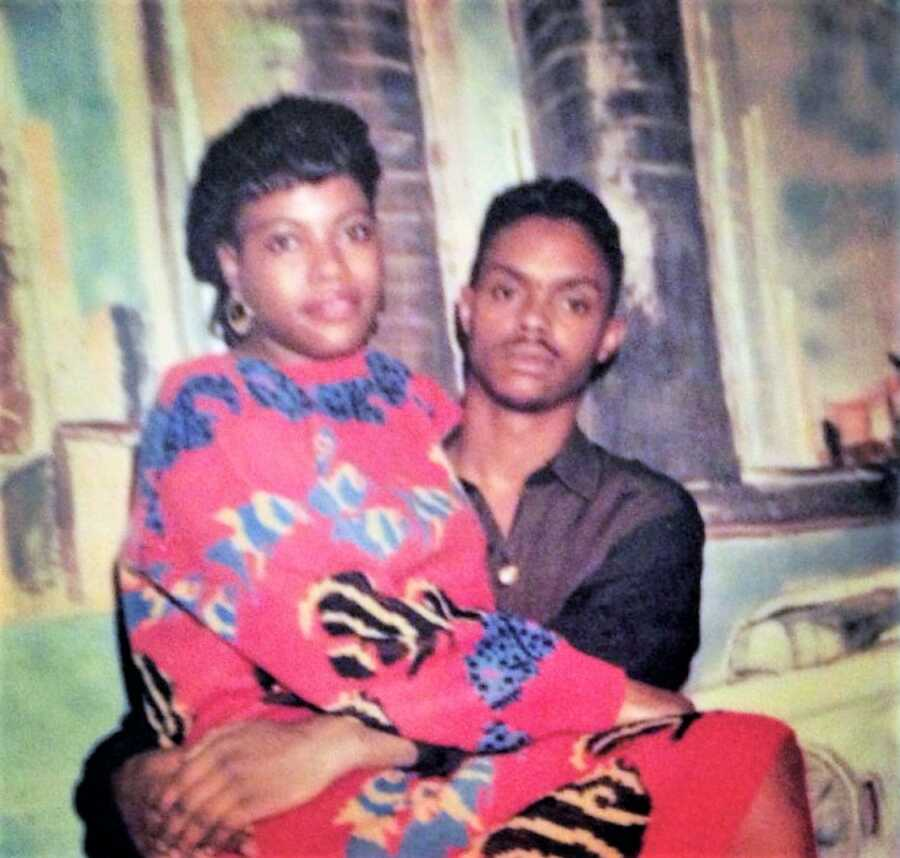

Center the child, listen with your eyes and your heart, and never forget adoption changes a life, but only love and accountability make it better. He was born in Detroit in 1992, a child of the inner city, where the War on Drugs took fathers away. His mom stayed home with four children; his dad sold weed. It wasn’t perfect, but they were together until police arrested his father for carrying less marijuana than he himself would casually have decades later. With the leading provider gone, his mother stepped into the drug trade. That’s when the lights began to flicker out, sometimes literally.

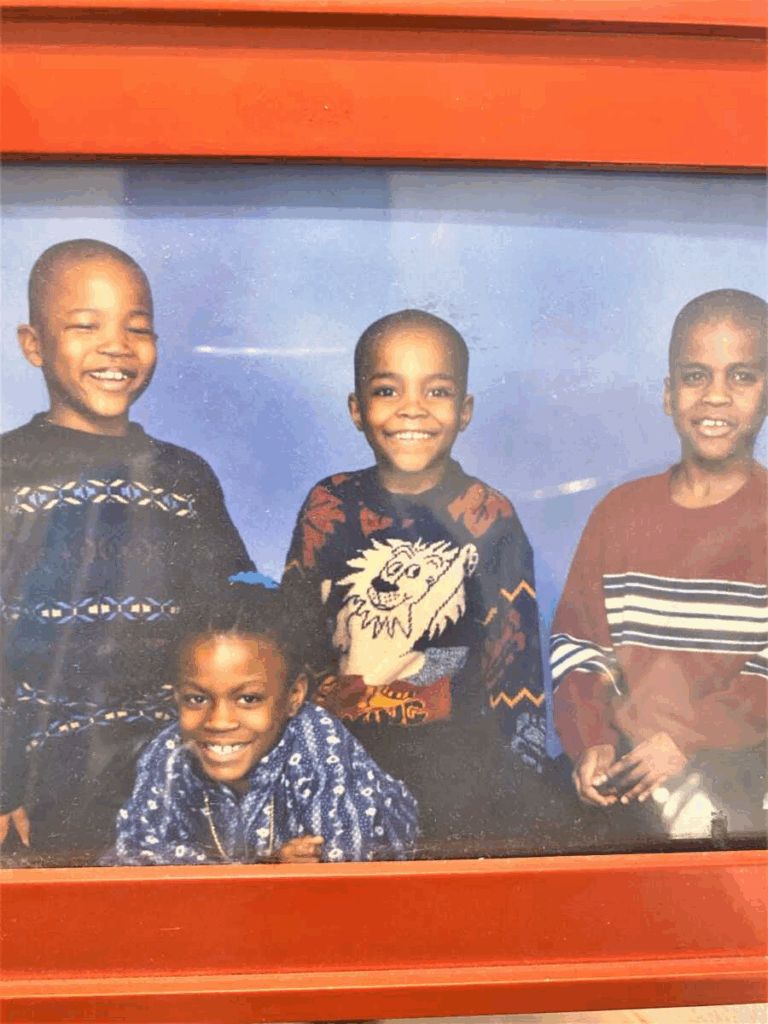

She disappeared on “business trips,” bills went unpaid, food ran low, and the men she dated brought danger into the house. One day, a SWAT team and a social worker burst through the door, guns up. Kids cornered. He thought he might die. Instead, he entered foster care and learned that some wounds don’t bleed on the surface. He bounced through roughly 30 placements: foster homes that closed, foster parents who hurt him, group homes that felt like jails. He rarely stayed long enough to learn other kids’ names.

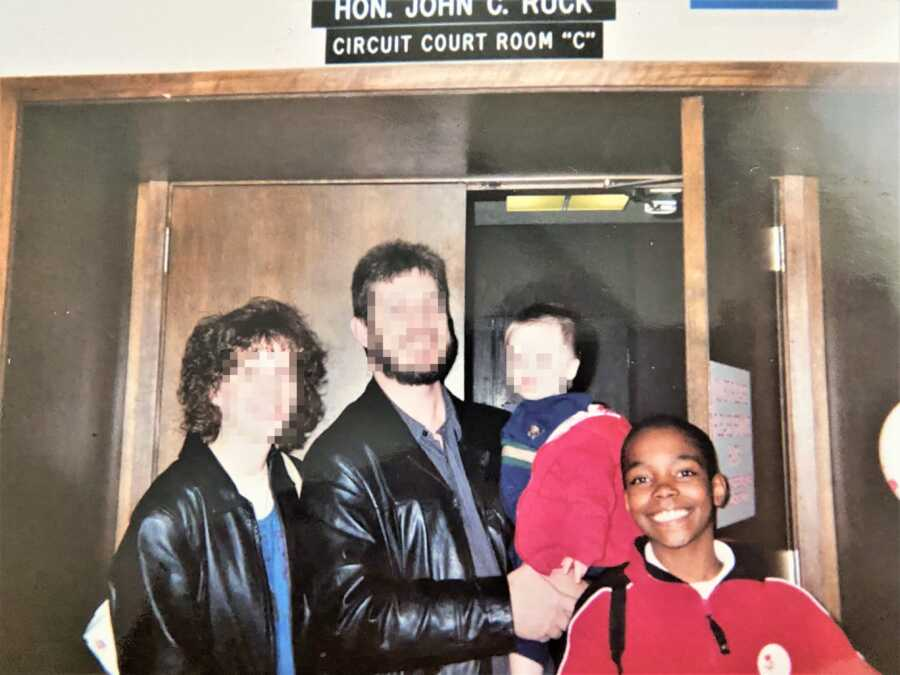

By eight, numb and desperate, he ran in front of a car, wanting out. The van swerved. He lived, then spent weeks in treatment. Hope was thin, but he held on to the idea that someone would choose him for good one day. At almost eleven, someone did. He was transracially adopted by parents who were not ready and did not see him. His adoptive mother’s pain around infertility became his burden; their strict religion turned his being openly gay into a problem to “fix.”

He felt more like unpaid help than family, doing yard work and housework, while their biological kids did none. At fifteen, his adoptive mother said she didn’t want him anymore and left him on the street. That goodbye never reversed. Adoption gave him a different life, not a safer one, and without the support he would have had if he’d aged out of foster care, he was alone. He couch-surfed, then ended up homeless, and was pulled into sex trafficking.

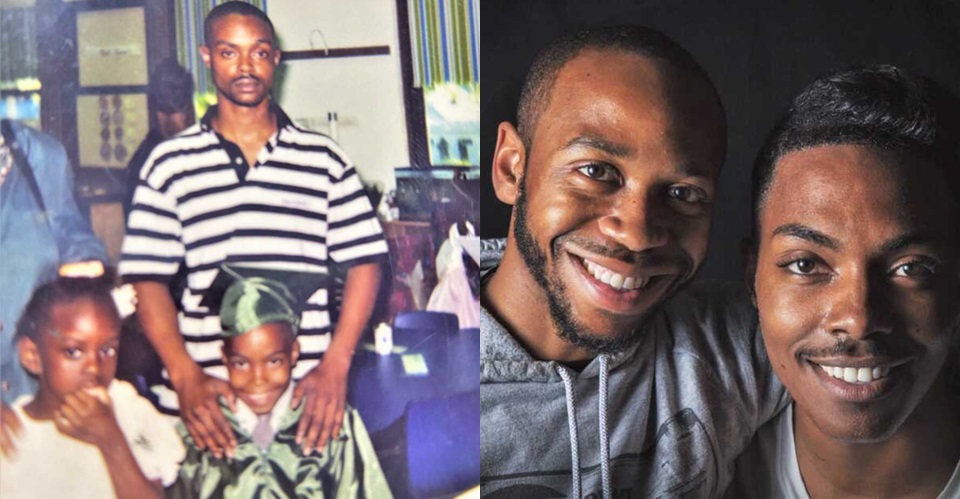

Still, some part of him refused to disappear. He got a GED, went to college, and met Kristopher, who would become his husband and anchor. With Kristopher at his side, he reconnected with his birth family. He asked his mother the most challenging questions: why she hadn’t saved him, why it went the way it did. She apologized, and they began to make new memories. For a while, there was light: trips together, Disney days, a sense that a circle was closing. Then tragedy struck again. His mother and sister died in a car accident. Loss returned like a familiar storm.

Even in grief, the past kept shaping the present. Because he’d been legally adopted, he didn’t have the automatic rights to handle his mother’s and sister’s affairs, yet he paid most of the funeral costs. A funeral director told him he “wasn’t her son.” That sentence still stings. He could have folded. Instead, he put his story to work. He wrote a memoir, “Wards of the State,” as part of a trilogy, to show what the system feels like from the inside.

He began training foster parents and social workers, sharing what kids need: safety, consistency, and adults who listen to behaviors as much as words. He used his platform to push for reform, including adoption annulment, so adult adoptees can legally end ties with abusive adoptive parents if they choose. He talks plainly about how foster care and adoption can help or harm, depending on whether the child is truly centered.

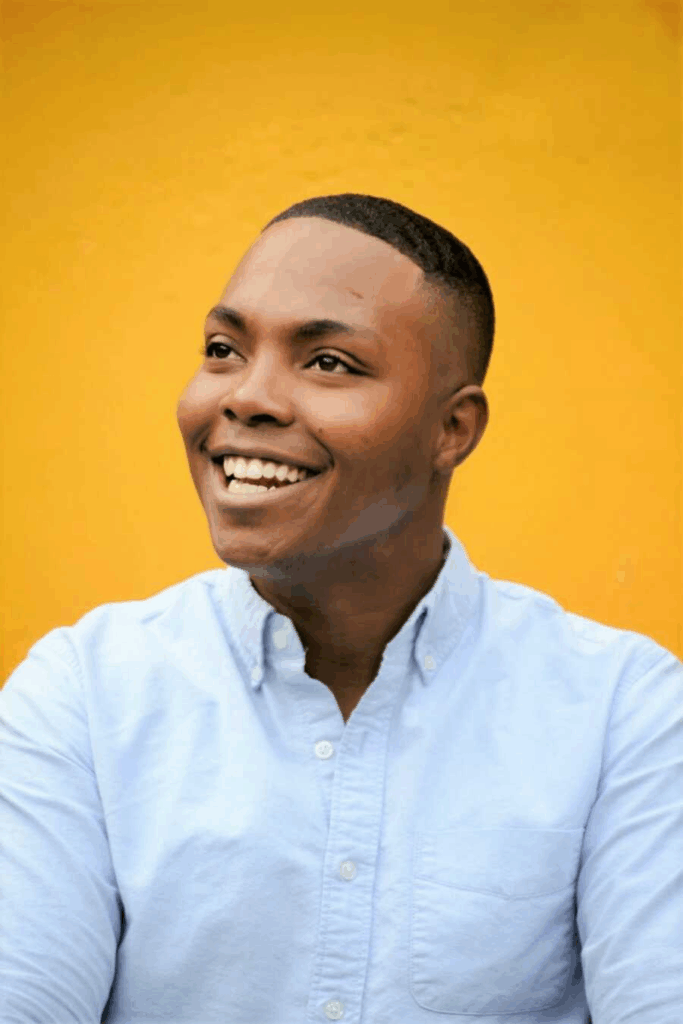

When he stands on a stage in a brown suit or smiles into a camera, it’s not because the past was easy. He learned to carry a torch through the dark and hold it high enough that others could see their path. He knows pain doesn’t cancel potential; it can teach purpose. He knows that a chosen family can be a real family. And he knows the system must change so kids don’t have to survive what he did just to become themselves.