This wasn’t a picture-perfect story; it’s a family built on a thousand hard yeses, and love that keeps showing up anyway. As a kid, she taped a news clipping to her doorframe so she wouldn’t forget to pray. It described a brutal civil war in Congo, militias fighting, families torn apart, and unspeakable harm to women and children. At twelve, she couldn’t make sense of the cruelty, but she knew one thing with certainty: she wanted to help. In her young mind, that meant adopting someday, saving as many children as she could safely love. Years later, she married, and adoption was never up for debate. After their third biological child, her husband nudged them to move before life grew too full.

They joined an adoption class at church and learned about foster care. Friends stood up and told the truth: court delays, family visits, challenging behaviors, heartache. Nothing sounded easy. Yet both felt a quiet push in the same direction. They looked at each other, half laughing, half scared, and said, “ So this is it.”

That sense of calling became their anchor when storms came. It steadied her during the nights she wondered why they had chosen this road. The first call arrived at 3 a.m. on November 14. A caseworker said a little boy at the hospital needed a home; his parents were homeless, and he had to be discharged. They said yes in seconds, and Andrew was asleep under their roof before sunrise. His birth mother worked her plan, and in eight months, he returned to her. They knew reunification was the goal, but their hearts broke anyway.

Life moved them to Seattle, where they welcomed two more children, Sam and Charlie. They kept in touch with Andrew’s mom through several moves and two more babies. Then came a report of neglect. Three siblings, ages two, one, and six months, were taken and placed three hours away. Because they lived out of state, they weren’t considered. She left weekly voicemails that were never returned and prayed for a clear answer: either open the door or help her let go. The next day, while they walked through the zoo, the caseworker finally called back.

The worker was blunt; no one calls to check on foster kids. What did she want? She told her about Andrew’s early struggles and the care he’d needed. Over the following days, the worker’s tone softened, and the whole picture appeared. Parental rights were moving toward termination. The foster mom loved the baby but wouldn’t adopt all three; Matthew had serious health needs; Andrew, now three, had severe behavior issues. A group home was on the table. She couldn’t stay quiet: they would take him. Then the interstate tug-of-war began.

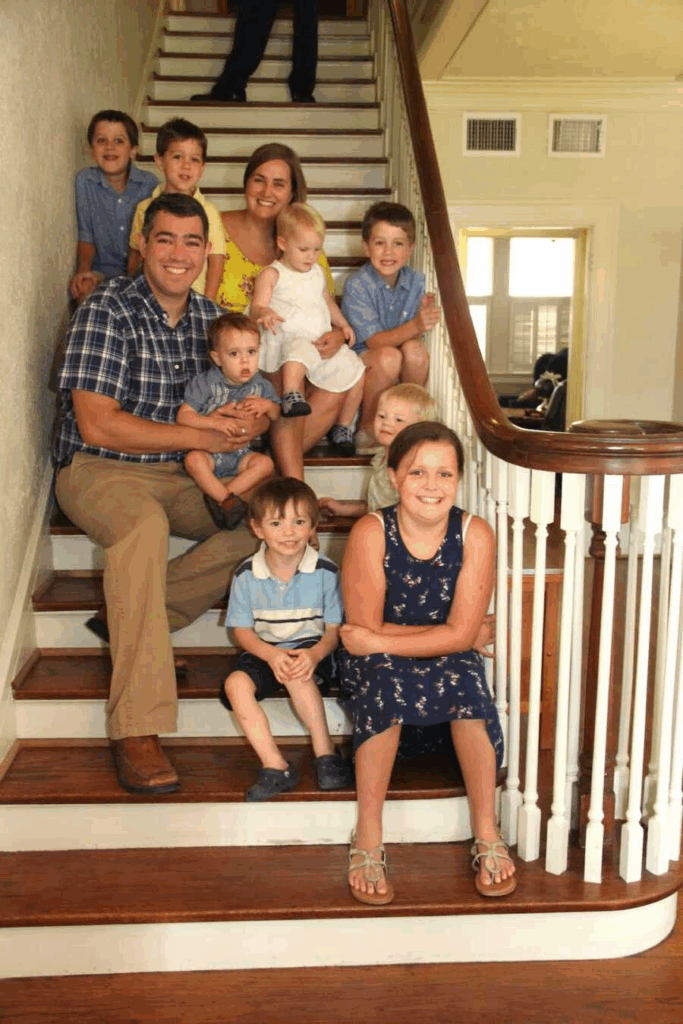

Texas would not allow adopting just one child, and Washington would allow only the “lowest-risk” child. Texas said they had to move back if they wanted all three. So they sold the house and cars in a month and returned to Texas. He, Matthew, and Hannah came home on Andrew’s fourth birthday. They stepped into this new season with eyes open. The training had told the children that they might be delayed at first, then catch up once they felt safe and attached. No one had prepared them for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. After years of therapy and waiting for the turnaround that never came, she dug deeper, found records that contradicted earlier denials, and pushed for evaluations.

Some professionals dismissed her. They flew to a specialist in California and got the diagnosis they suspected. From there, advocacy became part of her daily life. She explains that FASD is a spectrum: children may look typical but struggle with processing, impulse control, judgment, and cause-and-effect. It’s more common than many realize, often overlaps with other conditions, and could make independent adulthood very hard. Their kids live with multiple challenges, developmental delays, ADHD, mood and anxiety disorders. She and her husband hold two truths at once: the odds of complete independence may be low, and their commitment was unwavering.

She was honest that most days were hard. That doesn’t shrink her love; it stretches it. And when other parents say they’ve done the attachment work and nothing makes sense, she urges them to consider FASD and seek targeted services. She wants to be the person who calls back, the one she needed at the zoo that day.